As the story goes, Roddenberry conceived and shot his pilot episode for Star Trek, a property he described as a “wagon train to the stars.” The telefilm – titled “The Cage” – cast actor Jeffrey Hunter in the role of Captain Christopher Pike, captain to the Federation starship Enterprise on its mission to explore space. The particulars of the installment explored Pike’s run-in with the Talosians, a species of alien using their mental powers to essentially manipulate captives to do their bidding. When all was said and done, network executives ultimately rejected the pilot, deeming the story “too cerebral” and/or “too intellectual” for television audiences; but they liked enough of what Roddenberry and his team produced to ask for a second attempt, an astonishing rarity in the world of entertainment. Inevitably, Star Trek emerged, this time with William Shatner at the helm as Captain James T. Kirk, and most readers know the rest of the story.

What stays with me – as a ponderer about Science Fiction and Fantasy properties in general – is that castigation of ideas being “too cerebral.” I think that studio executives have long considered their viewership as people who don’t like to think too deeply about anything once they get home from work and plunk themselves in front of the television. They seek out programming that is light, inoffensive, and escapist. They don’t want to be mentally taxed. They don’t want to be academically challenged. Sure, such a perception is more than a bit insulting, but – only so much as it applies to the wider output of Roddenberry – the corporate administrator may’ve been on to something.

Not long after Star Trek’s cancellation from NBC’s lineup, Gene was hungry to get back into the game of weaving SciFi stories for the audience his show had justly earned. In the few short years since Kirk and his crew ended their exploration of the stars, the storyteller assembled Genesis II (1973), Planet Earth (1974), and The Questor Tapes (1974). These were three noble attempts to once again go where no one had gone before, and yet – for reasons not all that much different than what Gene had heard before – each failed to receive a green light to go into series production.

It seemed that – for the time being – “too cerebral” was a sign hanging around the man’s neck.

How interesting was it, then, that the last (and best) creation of these three – The Questor Tapes – centered precisely on perhaps “too cerebral” android searching for nothing more than its place in the world.

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Project Questor is the brainchild of the genius Dr. Vaslovik, who developed plans to build an android super-human. Although he disappeared and half of the programming tape was erased in the attempt to decode it, his former colleagues continue the project and finally succeed in creating Questor. However, Vaslovik seems to have installed a secret program in Questor’s brain. He flees and starts to search for Vaslovik. Since half of his knowledge is missing, he needs the help of Jerry Robinson, who is now suspected of having stolen the android.”

For some folks, ambition knows no bounds.

In the case of Gene Roddenberry, ambition was just part of the day’s work. Maybe even a walk in the park, for that matter.

In 1965, he gave mankind’s ambition to explore strange new worlds a weekly procedural, and the award-winning franchise Star Trek was born. Yes, like any program forced to work within the boundaries of television production, it had its narrative highs and lows, and yet – in three seasons – it showed mankind one possible future if we could put our petty struggles behind us. In doing so, we’d break the bonds holding us to this world to venture out there … wherein our descendants would come face-to-face with other species still struggling with their own petty struggles, and we’d show them a new way forward.

Who would’ve known that one of Gene’s later attempts was to plumb the depths of the human soul?

The Questor Tapes was reportedly the next truly big thing for the creator after Trek. Rumor has it that this one was received favorably by network suits, so much so that it came very close to realizing life as a regular show. I’ve read that, ultimately, it was Roddenberry himself who turned down the chance to see it added to the broadcast dial because those same executives wanted to institute so many changes to the foundation that it wouldn’t resemble his preferred inspiration. (IMDB.com reports that twelve scripts were prepared for a possible first season.) What those changes were exactly we might never know, but perhaps the greater crime here is that Questor could very well have been as compelling and as groundbreaking as Trek was before it.

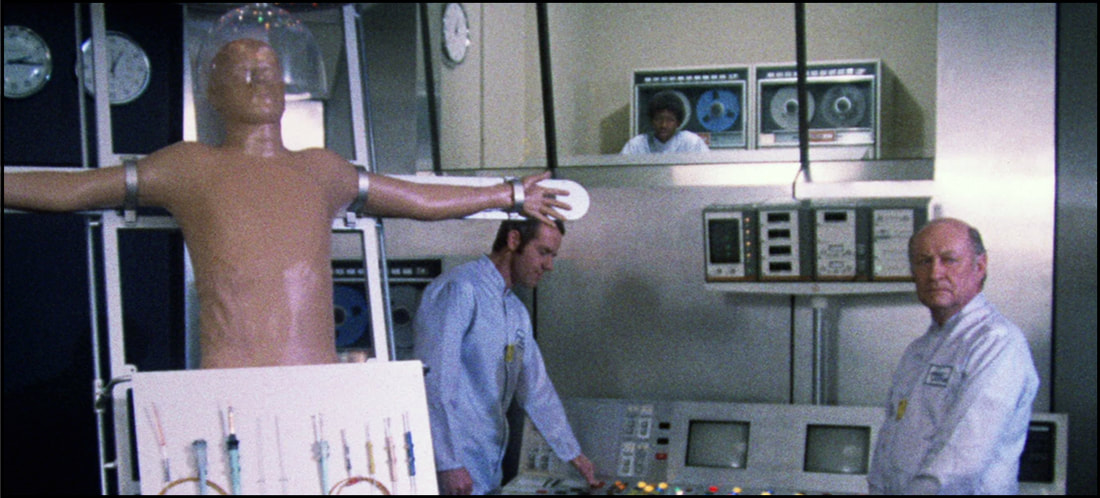

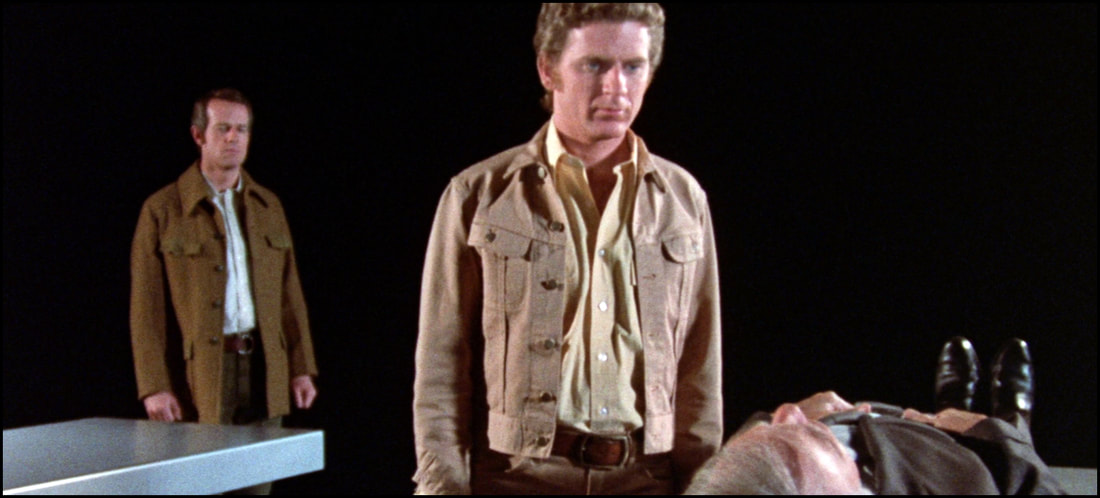

Questor (played by Robert Foxworth) awakens on a laboratory table not long after his builders were given signs of his catastrophic systems failure. It would seem that event was meant as a distraction which would ultimately the android to escape. As his programming was left a bit incomplete, Questor recruits the scientist most involved in his assembly – Dr. Jerry Robinson (Mike Farrell) – and, together, they set off in a race against time to defuse the bomb in the robot’s chest and to find his missing designer, Dr. Vaslovik (Lew Ayres), thus unlocking the secret behind the automaton’s origins.

In the end, Foxworth employed a tactic not all that dissimilar to what actor Brent Spiner did roughly over a decade later when Roddenberry crafted his android Lieutenant Commander Data for Trek’s return to the broadcast airwaves with Star Trek: The Next Generation. Both Foxworth and Spiner crafted an undercurrent of what I’ll call pure ‘roboticism’ – a coolly mechanical approach to movement and expression which gave the appearance of a manufactured being mimicking that which his builders achieved through programming. Occasionally artificial if not downright stiff, both actors moved and spoke with a practiced cadence, varying movements and inflections as their respective roles allowed for a little bit of human nuance. A smile might be forced, but its intentions were clearly authentic; and I’d argue that Spiner and Foxworth should be recognized as industry pioneers for having accomplished so much with so little.

As a counterpart and traveling companion, Farrell was more than a bit dull, so much so that I failed to feel at any time that he was committed to the whole affair. Some of this reception could be owed to the fact that, debatably, his character feels all too often like a bit of an afterthought in the script – so much of the action necessarily revolves around Questor, his mission, and his behaviors, etc. – and this ends up with having the actor play ‘the straight man’ a bit too often. When you’re playing second fiddle to an actual fiddle and the fiddle is inevitably more interesting, it can be hard to leave a lasting impression even on small scenes; and – had this show gone to series – it would’ve been fascinating to see what more could’ve been done with the ‘scientist on the run’ theme. Given that scientists historically gravitate toward an ordered existence, Robinson might’ve emerged as much the ‘fish out of water’ as was Questor … but, alas, we’ll never know.

Also along for the first and only ride was screen veteran John Vernon. In the guise of Questor project head Geoffrey Darro, he’s cast as an administrator who’s hell bent to see the android brought to life, even if that means throwing proper protocols out the window despite the possible emerging threat to mankind. With as little as a glance, Vernon made mincemeat out of anyone subservient to his wishes and desires in plenty of other films; so his casting in this role made perfect sense (perhaps too much so), but Roddenberry and Gene L. Coon’s script gives him an epiphany (and redemption) in the last act that felt a bit too orchestrated for my tastes. Again, he’s good, but – ahem – he wasn’t that good to sacrifice himself for the greater good.

Frankly, Questor isn’t all that grand, but like Roddenberry had been warned before it’s all a bit “too cerebral” at times … and that’s why I would’ve loved to see this one realized as a series. While it understandably would’ve been softened a bit here and there to fit that weekly broadcast mold as well as conform to network executives’ expectations, it could’ve been dynamic to experience a slowly realized discovery of what it meant to be human at Gene and Robert Foxworth’s hands. I’ve always been a sucker for anthropomorphized robots, and this one – with its central figure uncovering a secret legacy alone that could’ve made for some fabulous yarns – felt humble and relevant in all the right ways. I have read some online suggestions that it remains an intellectual property kicked around from time-to-time with an attempted reboot. What with the still emerging discussion on the threats and opportunities facing mankind’s ongoing fascination with Artificial Intelligence, here’s one viewer hoping that nothing’s too cerebral to keep a do-over from happening.

The Questor Tapes (1974) was produced by Jeffrey Hayes Productions and Universal Television. DVD distribution (for this particular release) is being coordinated by the good people at Kino Lorber. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert, I found the sights-and-sounds to this brand-new HD Master (reported from a 2K scan of the 35mm interpositive) to be quite good. There’s a bit of grain in the last reel involving some footage shot in the wide open outdoors, but a massive influx of light can highlight the fact that this was all shot on film, after all. Lastly, if you’re looking for special features? The disc boasts a textless trailer and promo, along with an audio commentary from film historian Gary Gerani. It’s a decent collection, especially given the fact that Questor remains a largely forgotten project.

Recommended.

Though the actors might appear a bit clunky in their delivery, the ideas and concepts at play across The Questor Tapes remain relevant even to this day: not only will some scientist achieve constructing a lifelike android, but society inevitably will have to decide what to do with it for the purpose of peaceful coexistence. While Roddenberry wasn’t perhaps the first in entertainment to posit these concepts, he clearly had the know-how and ability to craft scripts and stories that made the viewer think about them. It’s a shame Questor didn’t make that leap from prospect to ongoing series as it arguably would’ve proven once more that Gene was the go-to source for bold and innovative yarns pushing society to see what magic and mystery the future could hold.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Kino Lorber provided me with a complimentary Blu-ray of The Questor Tapes (1974) by request for the expressed purpose of completing this review. Their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed