Though some have argued otherwise, I’ve honestly always chocked up interest in the end of the world as we know it based on the popularity of Australia’s Mad Max (1979) and its vastly better sequel Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981). The films sprang (in part) from the fertile imagination of director George Miller – along with screenwriting contributions from James McCausland and Byron Kennedy on the first film as well as Terry Hayes and Brian Hannant on the second. A young Mel Gibson truly emerged as a marquee star in the flicks, playing a cop-turned-vigilante in a world down under sent quickly into decline as a result of our planet slipping into the day of collective reckoning following a major global war. Both films were rewarded with critical and commercial acclaim, so – in the era where imitation is the sincerest form of flattery possible – filmmakers everywhere sought to tap into such doom and gloom with hopes of reaping similar box office receipts.

As tends to happen as a consequence of films being made quickly and only in pursuit of the mighty dollar, many of these lesser Mad Maxes were not only incredibly inferior but also monumentally forgettable. Little attention was paid to plot, character, and circumstances – perhaps the three greatest attributes that Miller and his crew got right – and sanity was sacrificed at the altar of creative costuming, hard-boiled dialogue, and decked-out muscle cars. Rushed through production, these features were either unceremoniously dumped into theaters or deposited straight to home video. If this is what the audiences wanted, then studios and independent filmmakers sought to deliver the goods as soon as was humanly possible, all in hopes of capitalizing on the latest trend at the cineplex.

One of the biggest purveyors of – ahem – cheap imitation was Italian B-Movie auteur Enzo G. Castellari.

In fact, Castellari dipped so deeply into this well that he bathed in the magical waters not once, not twice, but an incredible three times. His 1990: The Bronx Warriors (1982) depicted a devasted New York City overrun with gangs emerging on the cusp of Armageddon. In 1983, he went back (thematically) to the Big Apple for Escape From The Bronx which pitted the last survivors against extermination squads. In between those two releases, the writer/director completed Warriors Of The Wasteland (1983) which some have called the best of the trio. (Mind you: even if it is the best, that still isn’t saying much!) In it, a pair of nomads find that there’s safety in numbers when a bloodthirsty crew of religious zealots set their sights on wiping humanity out once and for all.

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Two mercenaries help wandering caravans fight off an evil and aimless band of white-clad bikers after the nuclear holocaust.”

Throughout the 1960’s and into the 1970’s, Italian filmmakers put their particular stamp on the Great American Western, and – thusly – the ‘Spaghetti Western’ was born. These films were, chiefly, shot in Italy where production costs were low; and the bulk of these storytellers sought to emulate the visual storytelling sensibilities of director Sergio Leone. Also, the lion’s share of these films cast American actors in the leading roles, thus guaranteeing the ‘bankability’ and marketability of these oaters around the world and not just in Europe. Despite varying wildly in quality, the Spaghetti Westerns undoubtedly left a mark on film history by both changing the way business was done as well as culturally influencing directors around the globe to follow in such stylistic footsteps.

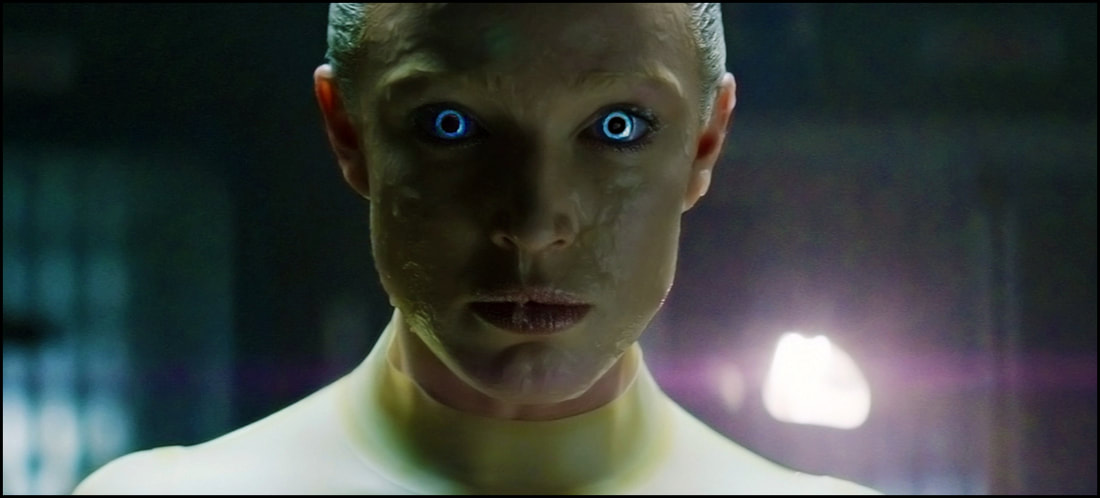

For all its placement in the future, Warriors Of The Wasteland (aka The New Barbarians) is thematically little more than one of those Spaghetti Westerns. Its two heroes – Scorpion (played by Giancarlo Prete) and Nadir (Fred Williamson) – are lone gunslingers transported from another time and another place into tomorrow. Their horses are replaced by futuristic automobiles. Scorpion’s pistol is of the laser-firing variety instead of the classic six shooter, and Nadir – his somewhat savage, dark-skinned associate – chooses the bow-and-arrow as his weapon of choice. Though their escapades pack a more explosive wallop than did The Lone Ranger and Tonto, this construct – nomads on patrol – is the foundation upon which Castellari built this colorful vision.

Need more convincing?

Well, the first half of Wasteland spends most of its time introducing both characters and their mutual adversaries: the Templars are a white-clad religious sect whose leader One (George Eastman) believes he’s been chosen by God, Nature, or whatever force remains in this broken universe to cleanse the Earth of the dregs of humanity who have somehow survived the Apocalypse. Like missionaries who went out into the West with a religious conviction all of their own, One remains committed to his own vicious form of salvation; and he’ll stop at nothing to see anyone who stands in his way – man, woman, or child – dispatched into the great hereafter. Though they’re painted as quintessential outlaws, an argument could be made that the Templars are little more than villainous cowboys who’ve lost their way. Redemption is only possible if they clean what’s left of the world of the filth.

Then how about the caravan of survivors who make their appearance in the second half of the picture? What might they resemble from a traditional oater? If one thinks of them like a wagon train heading out into the great outback in hopes of finally finding a place they can call home, then the comparison of Wasteland as a Western is undeniable. Like those settlers of old who would arrange their wagons in a closed circle, these fighters do the same, albeit here the circle is made of their broken and dilapidated automobiles. They live in their own little mobile commune, and they band together to defend everything that’s theirs when the Templars finally descend upon them.

At this point, I realize that there may yet be one or two holdouts. Persuasive arguments aren’t always convincing, and that’s why I saved the best piece of evidence until the last. Bear with me.

As tends to happen in Westerns, our chief hero – in this case Scorpion – suffers a fairly dramatic beatdown at the hands of his enemies, and the same takes place in Wasteland. Scorpion is captured. He’s strung up by his arms and legs in what services as a town square for the Templars, and One implores his minions to do their worst with him. It’s even suggested – though I’ll admit the filming of this was a bit confusing – that he’s anally raped by One, a torture I’ve read film scholars ascribe to a sub-culture of Italian films. After this, he’s mostly left for dead, giving Nadir the opportunity to swoop in, rescue the man, and put him back on the road to recovery.

Inevitably, all roads lead back to the caravan, and this is precisely where the Old West style showdown in the street is so aptly staged by director Castellari. Scorpion returns, laser gun on his hip and even the traditional Western poncho over his shoulders. It’s all arranged and photographed just like any classic gun draw, and if that doesn’t convince you of my perspective on the whole affair then you’re two mules shy of a wagon train!

None of this is to dismiss the problems inherent within the picture, and there are quite a few. Castellari’s vision of tomorrow is clearly hamstrung by the low-budget nature of Italian film production. While Scorpion is outfitted with a reasonably impressive muscle car (with just enough accessories added aboard to give it that otherworldly look), the rest of the vehicle fleet are these – gasp! – dune buggy style creations that probably evoke more laughter than they inspire terror. Akin to something out of Roger Corman’s Death Race 2000 (1975) if filmed in a senior retirement community, they just don’t evince that kind of grit, oil, and desperation as anything in the aforementioned Mad Max. By comparison, these transports ‘whine’ instead of chug like the traditional autos, and the fact that they look like their top speed might be 20 or 30 miles per hour certainly makes all chase sequences incredibly underwhelming.

Warriors Of The Wasteland (aka The New Barbarians) (1983) was produced by Deaf International and Fulvia Film.

(Mildly) Recommended.

While not achieving mainstream viability like the Mad Max films did, Castellari’s Warriors Of The Wasteland is, at best, an interesting diversion into a low-budget Apocalypse. Lacking some of the muscle required to truly sell the end of the world as we know it, the film coasts – as do its gnarly dune buggies – at unscary speeds far too much of the time. A few scenes resonate much the way the Italians Spaghetti Westerns did, and I say that there’s plenty of small favors in here to be thankful for. Still, Williamson hams it up just enough as an archer shooting explosive-tipped arrows, and rarely have bad guys blown up so good.

For those who like these kinds of details, I viewed Warriors Of The Wasteland (1983) as part of the Sci-Fi Fever 20 Film Collection released by Mill Creek Entertainment in 2013, a purchase I made via Amazon.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed