Indeed, Alternate History has fueled much of SciFi’s growth beyond its core audience over the last few decades. Books like Harry Turtledove’s “The Guns Of The South,” Stephen King’s “11/22/63,” and Robert Harris’ “Fatherland” were popular both with established genre fans as well as readers who tend to traffic in more mainstream fare largely because they explored alternate outcomes for seminal events in history such as the American Civil War, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and World War II respectively. Motion pictures like Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Bastards (2009) presented an unconventional look into events that never quite took place during World War II; while flicks like The Final Countdown (1980) and the crowd-friendly Frequency (2000) questioned the morality of tampering with fate – even at its worst – in order to produce a more acceptable outcome. Even television has gotten into the business with programs like the BBC’s long-running Doctor Who, NBC’s Quantum Leap, Fox’s Slider, and UPN’s Seven Days questioning how a timeline’s subtle reshaping can produce devastating outcomes that reverberate across the space/time continuum. While I’m not suggesting each of these are perfect examples of Alternative History as its own unique category, I am underscoring that all of them share that unifying thread of “what if” that almost magically captivates us all … and will likely do so as long as storytellers weave webs for interested audiences.

Arguably, one of the better authors of the 20th Century to explore whole ‘what if’ perspective as it relates to Alternative History was the late Philip K. Dick. His “The Man In The High Castle” served as the inspiration for Amazon Prime’s streaming program of the same name, and the show recently bowed out of its original broadcast existence with the release of its fourth (and final) season.

I thought it apropos to sound off on it just a bit.

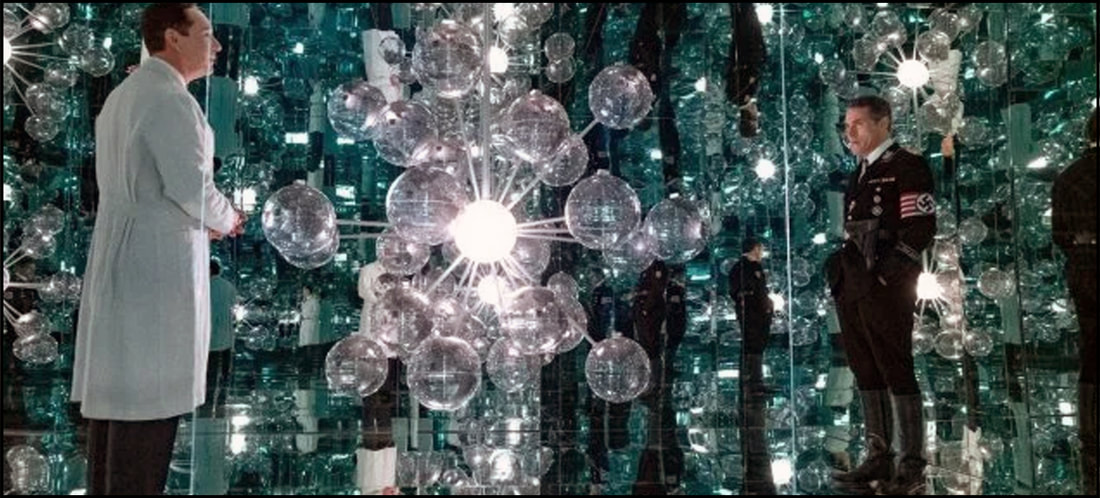

At the end of Season 3, Juliana Crane (played by Alexa Davalos) discovered that she had mastered the ability to move mentally between the various universes, thus escaping the clutches of the Third Reich but not without injury. As Season 4 opens, time has passed, wounds have healed, and yet our heroine finds herself still drawn to world of her birth with a desire to set things right. Eventually, an attempt on her life by universe-hopping agents serving Obergruppenführer John Smith (Rufus Sewell) propel her back into the Prime world, where she enacts a dangerous plan to end Smith’s reign once and for all.

Without divulging too many secrets (though I’ve already warned that there will be spoilers), not everyone returns to the popular program’s final season. Fan favorites are noticeably absent (some departures serve as essential plot points while others don’t), and I found it hard not to be affected by their nonappearance. Much of the High Castle’s past narrative appeal has been these characters’ various explorations of their own personal humanity and their struggle to maintain it when the greater world-at-large encourages an easier savageness (Nazism) or outright apathy (accepting one’s fate). As a result, there’s nearly no discussion of the Jewish plight (much less any discussions of faith except to the state), but maybe that was by design: after all, the Nazis weren’t all that fond of the Jewish people, now were they? Perhaps they'd wiped them all out by now?

Don’t get me wrong when I say that I thought all of this could’ve been handled better: and – just to be perfectly clear – my point has nothing to do with race, race relations, or people of any color (though I’ve no doubt some readers may infer otherwise). All I’m trying to say is that given the show’s history – race had really only come up tangentially in previous seasons – much of the final season’s West Coast storyline felt like clunky posturing. These developments never felt natural and organic, while the demise of the Japanese interest in occupying America against a growing militant threat did; and I think that narrative disconnect does a disservice to a more serious discussion of race the show could’ve easily begun earlier … but methinks no one thought of it until they knew they needed something of lasting critical import for their swan song of a season.

Now, if that’s nitpicking, so be it. Nitpicking is a great way to voice frustration over something one cares about, and The Man In The High Castle has been a fascination of mine (and a growing audience) since developed on Amazon. Even casual fans care about stories; political posturing at the last minute – regardless of who’s doing it or what program it’s a part of – cheapens a story whenever it’s tried. Why? Well, I’d say mainly because it pushes solely the ideological elements therein … and hasn’t that been our complaint against Fascism since it reared its ugly head?

And speaking about Fascists, what of John Smith?

Well, he fares about as well as any central villain can in any genre program.

He’s a flawed man who for reasons finally spelled out rather brilliantly in Season 4 has tied his, his family's, and his country’s future not so much to Nazi Germany as he has to his never-ending quest for power. With a name as common as ‘John Smith,’ methinks everyone knew his original fall from grace wasn’t going to be about grand schemes (though there is one here, which I’ll get to shortly). Instead, it was simply all over the need to be a good provider. When history called, Smith traded his humanity for bread and water. Given the circumstances, it’s an understandable betrayal but nonetheless necessary to put him on a path where turning one’s back on principle becomes the status quo.

Consequently, his moral epiphanies along the way up the political ladder are swallowed whole by his own wretched greed. Just when you think he’s learned his lesson, he proves otherwise, as is the case when the Jewish soldier he once aided he now deserts. He does this not because he’s written that way; rather, he does it to underscore that absolute power always has and always will corrupts absolutely. History accepts no less.

And, what, pray tell, of the ending?

Anyone who’s followed the media surrounding High Castle’s conclusion has undoubtedly stumbled across articles which try to “explain” the finale’s closing moments, some writers even going so far as to ask the showrunners what it all meant: third season’s portal between the parallel worlds has somehow mystically opened up across the various universes, and now regular Joes and Jills are simply walking willy-nilly into the Prime one. Was this meant to mean something greater about choice and chance, or will this go down in media history as Castle’s ‘jump the shark’ moment?

As humans, we possess an intellectual inclination to ascribe ‘meaning’ to events. (Here’s where I get a bit philosophical, and – be warned again – others may disagree. Such is life.) We do this not because it’s a display of intelligence but rather because grasping the ever elusive ‘meaning’ implies that we understand it. We understand Life. We understand Fate. We may not like it. We don’t have to accept it. But if we understand something, then we establish dominance over it. Psychologically, this gives each of us the ability to get beyond tragedies and failures, and it also causes us to celebrate our respective achievements along the way. We convince ourselves that ‘this’ happened only because ‘that’ happened first, and such rationalizations are the bedrock of truly being able to get through all of it intact.

Still, the wiser among us are quick to remind that accidents happen, and accidents are rarely if ever predicated solely on the results of happy little equations.

So do those last scenes mean anything?

Personally, I think not.

What I do think is that the writers were intent upon saying something cumulatively about the journey they shared with their audience, and perhaps this is all they could agree on. (I’m of a mind nothing more was really needed after Smith’s self-inflicted departure as that told me all I really needed to know about what awaits most despots.) Maybe it was an attempt to flesh out a measure of happiness from a tale so heavily steeped in dire circumstances, political skullduggery, and cultural oppression. Or maybe it was an honest trick to show that every cloud has a silver lining, even a cloud brought to mankind by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

You give it the meaning you want. I’ll give it whatever meaning I want. ‘Nuff said.

Juliana’s struggle – finding her place in history in a world suddenly rife with possibility – managed to retain as much gusto as it had in Season 1; and, for that, I suppose viewers will always be happy with much of High Castle. As often as she was the victim here, she pushed back to display only the best of her individuality. She’s the hero, the waif, and the Kingslayer, all rolled up in one, though she never quite understood which role she was meant to play until History called upon her to complete the deed.

I’d like to think that’s who we all are.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed