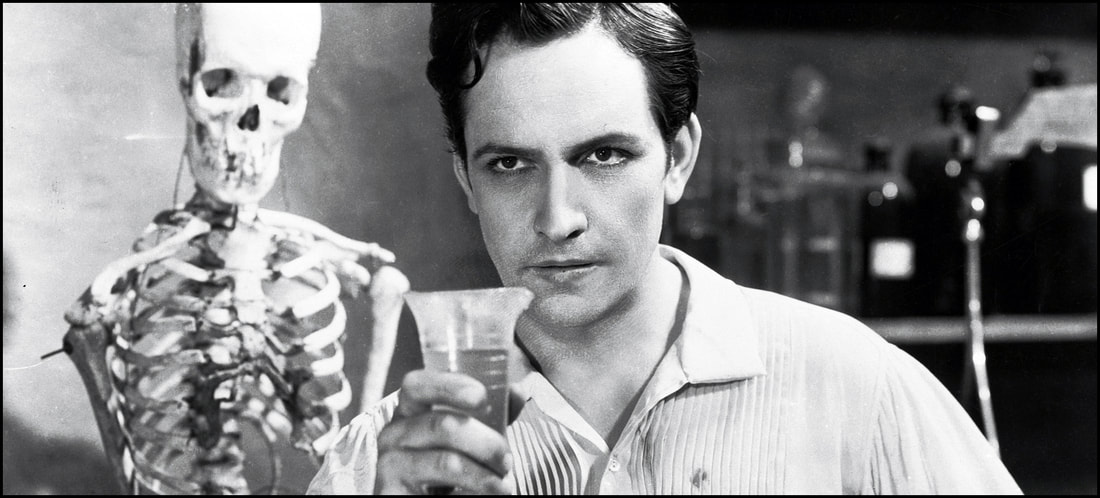

1931’s Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde – directed by Rouben Mamoulian – certainly wasn’t the first adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (first published in 1886); and yet the motion picture does have a few ‘firsts deserving of mention and celebration, especially given that’s precisely what we do in this space on SciFiHistory.Net. According to IMDB.com, this Jekyll had the honor of being the first picture screened at the first first film festival ever: the Venice Film Festival came into being in 1932, and it continues hosting some of the screen’s best nearly a century later. Furthermore, at a time when Universal’s productions were thrilling and chilling American audiences, it was Jekyll’s Fredric March – in the guise of the medicinally-tormented physician turned madman – who won Horror’s very first Academy Award ever.

Those are two feathers in an incredible cap, indeed.

Alas, it wasn’t even a decade after the film’s release that it was nearly forgotten, and such an oversight was deliberate. As Fate would have it, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer secured the rights to produce their version of the Stevenson story; and – in the process – they went out of their way to have the 1931 incarnation suppressed. Wikipedia.org suggests that the studio went so far as to local and destroy what they believe to have been all prints of March’s star-turning performance; and the feature was believed for many years to have been lost. Thankfully, it survives to this day despite a rather nefarious campaign to see it unnecessarily removed from history.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Dr. Jekyll faces horrible consequences when he lets his dark side run wild with a potion that transforms him into the animalistic Mr. Hyde.”

As impressive as the 1931 incarnation of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde is – and make no mistake as this one is very impressive for its day and endures quite well even today – it still includes some curious choices that I think lessen the experience.

In ways, it’s almost like director Rouben Mamoulian was experimenting at times with other ways to craft his narrative; and – as interesting as they might be – I thought the visual trickery occasionally got in the way of the story being told. There are a few sequences captured as if they’re intended to be first person – told directly from the point of view of Dr. Jekyll – and I found myself wondering why on more than once. For example, when he’s in the world of Mr. Hyde, such flourish makes more sense – the audience gets transported in such a way that they see the world through the eyes of a lunatic. But there just weren’t enough differences between the two perspectives – Jekyll vs. Hyde – to have the technique register as smartly as it probably could have, making it a bit of a misfire for me.

Setting aside my reservations with the finished product, there is just so much remaining that’s worthy of some unquestioned love.

Because this was made before the Hays Code went into effect (1934-1968), this Jekyll retains an incredible and noticeable undercurrent of human sexuality, something later iterations would temper if not ignore completely. For example, Dr. Jekyll expends a great deal of heartfelt expressions of traditional love for his fiancé, Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart). He speaks somewhat profoundly and poetically about his feelings for her, and she responds with equal almost Shakespearean aplomb. But such flowery language has no place in the exchanges between Mr. Hyde and Ivy Pearson (Miriam Hopkins as a bar-singing temptress); he’s prone to violence and torture in their moments alone, driven somewhat obsessed with her voluptuousness. Though I’ve read these romantic entanglements were not part of the original Stevenson tale, they’re introduced and handled so elegantly here one might wonder how they were ever possibly left out.

Still, what works best in all of this is March, so much so that his Academy Award win makes perfect sense. He handles the dual roles here with incredible ease, imbuing Hyde with an almost animalistic propensity to every subtle gesture while allowing Jekyll to possess that world-serving high-mindedness whenever he’s on screen. The actor clearly foisted this whole affair onto his capable shoulders, and I’ve read that audiences of the day loved it, making it stand alongside Universal’s monster universe as it should.

This one definitely earned its place in history despite the efforts of some who would rather have had it forgotten for all the wrong reasons.

Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (1931) was produced by Paramount Pictures. DVD distribution (for this particular release) has been coordinated by the fine folks at Warner Bros. via the WB Archive Collection. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert, I thought the pictures sights and sounds were very good from start-to-finish. As for the special features? Given the fact that I viewed this one on television, there were no special features under consideration.

Highest recommendation possible.

In the interests of fairness, I viewed Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde (1931) from a recent airing on Turner Classic Movies; and I was in no way, shape, or form beholden to anyone to produce a review. I did this one entirely because I wanted to, and I’m glad I did. This version is, arguably, one of the best out there.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed