Where do I begin?

Ugh.

I’ve often argued that Frank Herbert’s Dune is one of those elusive properties that just doesn’t lend itself to cinematic adaptations.

Now, haters, calm down: I’m not saying that the work can’t be adapted to the big or small screens because that’s already happened to my count twice – David Lynch’s version in 1984 as well as the Syfy-produced miniseries in from 2000. Both took somewhat differing approaches to the source material. Both have been acknowledged for their worth with a measure of accolades, nominations, and trophies. And both have managed against the odds to build respective cult audiences by having translated Herbert’s big ideas about spice and those who would control it into convincing spectacle in a manner that interpreted the material (“interpreted” being the key word here).

Still, ideas that work cerebrally – in the brain of readers – don’t always have the same kind of power visually.

George Lucas was one time rather famously asked about why he started telling his Star Wars space opera with the 1977 film, an installment mankind soon found out was actually ‘Part 4’ in a longer saga. (I’ll dispense with the whole “did he plan 6 films or 9 films?” debate because it really doesn’t matter here.) His answer was – and I’m paraphrasing – that all of the really fun stuff happens in the Original Trilogy. Expanding on it, he explained that the first three parts would be focused more on political skullduggery and galactic machinations; and he felt that audiences might not be ready for those ideas when he could instead deliver a much more traditional space Western for mass consumption. So he started there, built an audience, and then went back to tell the rest of the story.

As that’s the established chronology for releasing his films the way he did, Lucas clearly understood – as a storyteller – that there was something irreplaceable about characters being thrown into visible, understandable conflict as opposed to the vast information dump that takes place in Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 adaptation of Dune. There are only tinkerings with establishing the vastness of Herbert’s world, and yet because there’s so much volume to it the introduced lead characters – namely Paul Atreides (played by Timothée Chalamet) and Lady Jessica Atreides (Rebecca Ferguson) – end up feeling more like props to the wide, wide universe instead of people an audience are supposed to be interested in for the next 180 minutes.

In other words, imagine that George Lucas wanted the audience to know an extensive summary of what took place in Star Wars episodes I, II, and III at the start of A New Hope. How could he possibly accomplish this while also tugging at your heartstrings over Luke Skywalker’s anguish of being told to “wait another year” to go off and join the Imperial Academy? Is it more important that you identify with the Empire and the Rebellion’s shared history, or did he want you to join our intrepid youth on an adventure far, far away? I don’t have to think long and hard about that question at all, but Villeneuve’s construct here tried to have the best of both worlds, biting off far more than he could chew than was (perhaps) narratively possible with Dune as this cut presents.

In contrast, what did I learn about Paul Atreides, this universe’s young hero?

For all intents and purposes, I thought Paul came across largely as a moody yet good-hearted kid; but because there’s so very much more going on in his lineage it’s hard to dismiss the fact that he’s also presented as Christ-like very early in the film. Even the Fremen – Arrakis’ native people – see the boy as a spiritual figure. Villeneuve’s script quickly discounts this, insisting that they’d likely attributed such status on the villainous Harkonnens – but there’s no mistaking that Paul is not some everyman’s farmboy who would undertake the hero’s quest to become the galaxy’s last, best hope. From the outset, he’s not just different but he’s way different – special, gifted, royal, genetically superior – and therein might lie Dune’s biggest problem: audiences just can’t relate to him.

As others have observed, Dune is an intellectual property difficult to talk about except for people who are already familiar with it. I think this is not only true but also I believe it can be used to justify why audiences have never widely embraced the previous two iterations: Paul is a God figure – that’s certainly how he evolves in that universe – and we’re just ordinary Jacks and Jills. We don’t identify with gods, so we’re already separated from them emotionally. This doesn’t mean we don’t enjoy their stories; after all, the Bible is one of mankind’s biggest and longest running bestsellers … but we flock to it for reasons that are immeasurably different than why we vicariously experience narrative fiction.

Paul means little to me. Luke? I get Luke. I want to be Luke. I’ll fly the Death Star trench with him, and I’ll gladly join him on Dagobah for secret Jedi training, or I’d even stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a blazing lightsaber battle with Emperor Palpatine if Luke asked me to.

But … Paul?

He’s Christlike … so what does he need me for?

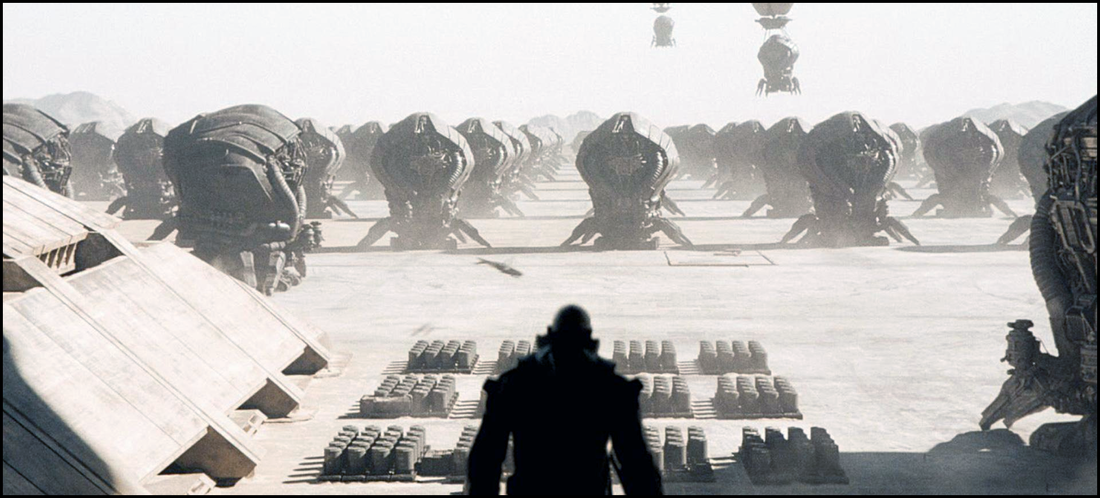

Now, categorically, none of this lessens the strengths of what director Villeneuve accomplishes visually. Clearly, he’s immersed himself in these worlds, and he’s spared no investor’s expense to bring them to life on the screen. He’s taken the wide, open, endless desert seas of Arrakis and made them visual poetry – certainly real enough for fans of this franchise to enjoy again and again, much like Marvel fans flock to their superhero yarns for endless repeats. He’s given breath to the political machinations of a galaxy that really only existed before in Herbert’s series of books in such a way that I’m sure folks will be reminded of Peter Jackson’s The Lord Of The Rings and HBO’s Game Of Thrones adaptations. These ships and vehicles are unlike anything many have ever seen before, and I’m convinced these production designs will become influential in the years and decades ahead for other filmmakers who want to tackle similar challenges with the kind of scale employed here.

But for all those strengths, I still found this Dune a bit hollow.

There are moments that work, and they’re unsurprisingly the times when our cast of characters are finally thrown into some jeopardy. Once Hell breaks out? That’s when Dune rises. Since that doesn’t happen until the last third of a nearly three-hour picture, I’m expected to absorb two hours of set-up for a relatively small return on investment. Momoa shines here, though his contribution is pretty slim; and Ferguson gives a performance that tried to ground audiences into the relationship she shares with her destined child. For what it’s worth, Oscar Issac as ‘Duke Leto Atreides’ never quite worked for me, seeming a bit too young for such an esteemed position in the galaxy; but I did appreciate the effort. Still, lacking any real emotional connection to these characters, it all ended up being small moments in some very good CGI.

Alas, the picture ends with a perfunctory cliffhanger, though a not entirely successful one. Knowing where this story was heading, I was aghast that it ended just when it was all getting good. Given that neither Warner Bros. nor Legendary Pictures have greenlit a sequel, this may end up being the most unsatisfying cinematic relationship for genre fans since director Ralph Bakshi left audiences on the precipice of all-out war with his 1978 unfinished adaptation of The Lord Of Rings … and I still haven’t forgiven United Artists for that.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed