Blade Runner 2049 Mounts A Slow Climb To A Treacherous Peak In Cinema History

It isn’t to say that I wouldn’t welcome the opportunity (especially if you're reading this, major newspaper outlets!); rather, it’s that – on occasion – I find it hard to have something interesting or relevant to say “right outta the gate” with some projects. As a viewer, I do tend from time to time to prefer to think about a film or a TV show before sounding off … and that’s definitely the case with Blade Runner 2049. As a film, it’s richer than most. As a meal, it’s meatier than many. It’s exactly the kind of flick I like to ruminate over a bit before I fully commit to some thoughts, and now that I have I think I have something to say.

Frankly, it might not be all that different from what’s been put out there already, but that won’t stop me from saying it.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for my final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

“Officer K (Ryan Gosling), a new blade runner for the Los Angeles Police Department, unearths a long-buried secret that has the potential to plunge what's left of society into chaos. His discovery leads him on a quest to find Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former blade runner who's been missing for 30 years.”

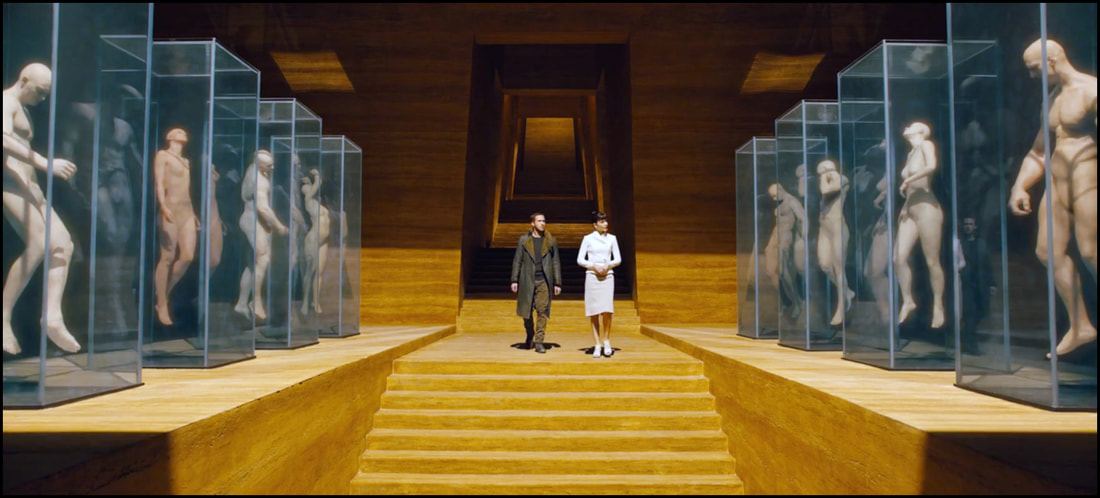

Yes, everything you’ve probably already read about Blade Runner 2049 is – most definitely – true: it’s a visual masterpiece, one of the best of the modern filmmaking era.

Clearly, director Denis Villeneuve is a fan of the original as I’ve no doubt he spent hours crafting the look of 2049 almost entirely on the Ridley Scott feature, and I suspect film students and scholars will spent the next thirty-five years dissecting the hidden (and not-so-hidden) meanings of each and every construct as they’ve done with the seminal inspiration. Hampton Fancher and Michael Green’s script smartly picks up the core elements of the older film and builds on them in ways that logically expand the universe created, showing not only a passage of time but also the consequences of technology further chipping away at our humanity, leaving even replicants only left with virtual companions in a world nearly void of any human contact.

Both the original and the follow-up -- as pure a sequel as can be -- share the distinction of being “stories” that require a certain amount of “storytelling” for the events to unfold. Neither project is heavy on exposition – visual or otherwise – and one might admit to feeling the passage of time itself while waiting for developments from one event to the next. Neither motion picture is heavy on action; both are tales requiring an investment of character in order for them to make the kind of narrative sense the viewer is rewarded with in the conclusion, but that’s quite possibly the greatest distinction I found between them separately.

Scott’s Blade Runner was a yarn built around the parallel existential discoveries of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) and Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer): both men are driven personally to shape the unforgiving world they were built for, though Deckard’s shaping is owed more to riding out the ebbs and flows of his job at first blush. As the ride grows more intense, Deckard realizes he can take command – falling in love with Rachel (Sean Young), bucking the requirements of his police boss in pursuit of further bloodshed, etc. – so much so that he loses sight of his own civilization in the process. Necessarily, he’s fallen so far off the beaten path that he needs the bloody, primal clash and near-failure with Batty in order to have humanity restored to him. It's a kind of redemption, one that leads to an even greater but understandable sin.

For years, I’ve argued that the central idea behind the original film is the pursuit of mercy, perhaps the ultimate expression of (dare I say?) Godliness for we mere mortals. “God giveth life” is what we’re taught, and so much of human history deals with how “man taketh it” away. Blade Runner is the tale of two men chasing the shared demon for different reasons, Deckard because it’s all he knows and Batty because he wants to, relishes in the pursuit. In the end, it’s mercy that redeems both sinners: the hunted saves the hunter’s life in the final reel, and it’s the hunter then who reciprocates – showing mercy – allowing the hunted to die on his own terms.

The film and its characters seem to be entirely constructed instead to comment on humanity (or the lack thereof) in this bombed-out world of near-tomorrow, but these various ingredients don’t quite congeal into any single ‘moral of the story.’ K’s so inhuman he isn’t even provided a full name by his manufacturers. Lieutenant Joshi (Robin Wright) is a pale bureaucratic functionary who lives and dies by the job, once entertaining dropping her guard for some sexual facetime with her engineered subordinate only to dismiss it when he kinda/sorta rebuffs her. Luv (Sylvia Hoeks) is a replicant sternly dedicated to maintaining the corporate status quo no matter where such dedication takes her; her narrative counterpart – Joi (Ana de Armas) – is the only ‘human’ in all of this, and that’s ironic owed to the fact that’s she’s the film’s quasi-sentient hologram meant to represent near-technologic perfection, intimacy of the highest order.

Unlike Scott’s original, 2049 seems content with maintaining a stronger degree of individuality from start-to-finish: the players might interact (narrative conflict requires it), but they all seem to stay on separate roads, never gelling around a central message the viewer might relate to. And – who knows? – perhaps that’s all Villeneuve wanted to say about tomorrow, that no matter how technologically advanced we might be we’re still destined to live and die alone? Indeed, K’s last moments would seem to bear out such fruit; and – without spoiling the surprise – even Deckard’s final reveal might underscore how even reunions ultimately might be denied that which we all inevitable seek: human touch.

As an aside, I’m at a loss to understand why industry insiders believed 2049 would be some break-out box office superstar. Those of us familiar with the original know that it took its sweet time (along with several subsequent ‘editions’) to reach its deserved perch in cinema history. While Mr. Ford’s box office clout may’ve been overestimated by some, I tend to think Ryan Gosling remains a bit of a ‘critical darling’ at best; Hollywood creations rarely find blockbuster status entirely on the merits of ‘the work,’ and he still has miles to go before he sleeps (if you’ll pardon the expression). Also, today’s ADHD-obsessed audiences can’t sit for nearly three hours on a narrative payoff, especially one lacking constant explosions, a pulse-pounding score, and Marvel-designed spandex. In my humble estimation, 2049 always had a hill to climb, and I’m accepting this theatrical release as only its first step.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed