Flashforward to 2021: I earned some Amazon.com bucks via my credit card, and when I realized I had more than enough to spring for the latest Shout Factory release (why are these things so bloody expensive for a twenty+ year old film?) I figured it was a sign from God, the Universe, or whoever still sends signs. I ordered one up. It sat for a few weeks – secretly biding its time, secretly waiting and wanting for me to put it in the player – and I finally got around to it last night.

Going into the whole affair, I was aware that the feature was an adaptation of a Philip K. Dick short story (novella?). As a SciFi/Fantasy junkie – and one who’s read a good handful of Dick’s short stuff (his novels just haven’t quite tickled my fancy) – I yearned to finally come to grips with this incarnation. And I knew that it was headlined by none other than the original RoboCop himself – Peter Weller – perhaps very near the peak of his critical and commercial acclaim. Given these bona fides, I’d often wondered why Screamers failed to achieve wider success.

After a single view, I think I can answer that question.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the product packaging:

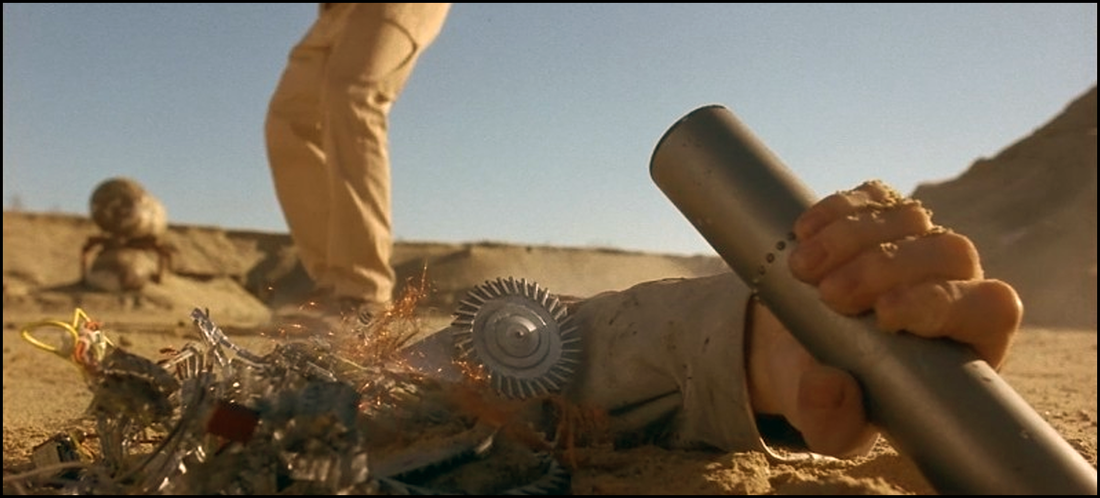

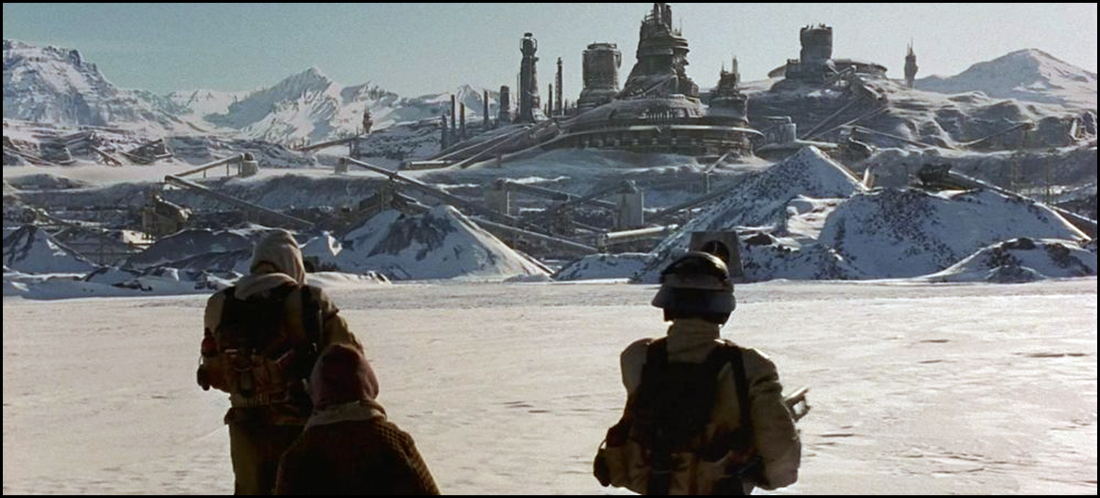

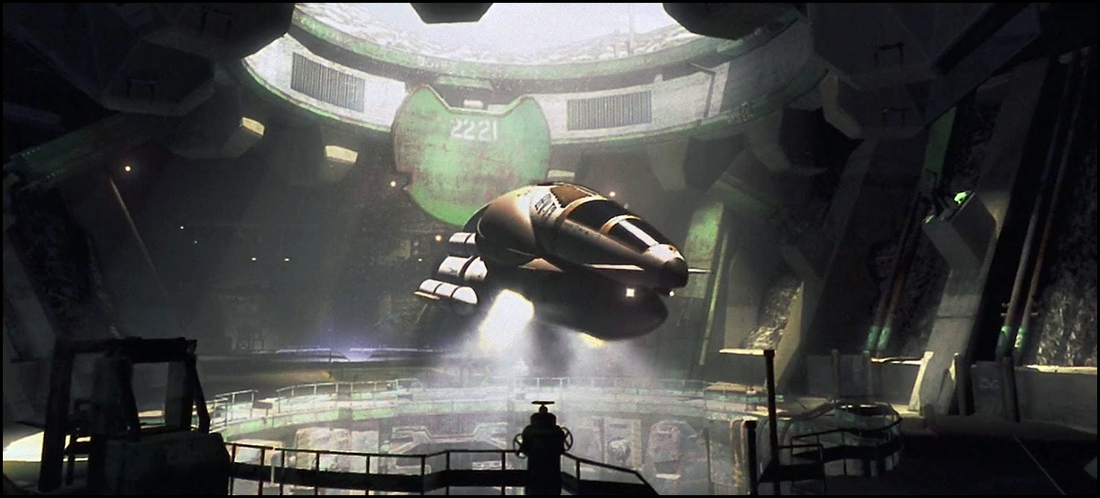

“The year is 2078. The man is rebel Alliance Commander Col. Joseph Hendricksson, assigned to project the Sirius 6B outpost from ravage and plunder at the hands of the New Economic Bloc. His state-of-the-art weaponry are known as Screamers: manmade killing devices programmed to eliminate all enemy life forms. Screamers travel underground, their intent to kill announced by piercing shrieks. They dissect their victims with precision, then eradicate all traces of the carnage. They are lethal. Effective. Tidy. And somehow, they are mutating … self-replicating into human form … and slaughtering every beating heart on the planet.”

I’ve long harped about films requiring so much set-up that producers or screenwriters are inclined to write an opening scroll. In short, I hate them. To me, they represent a qualifier that almost promises what to follow is bound to be an inferior product. And the longer they are? Well, that means the more inferior the product is going to be. I’d rather learn my facts organically and not have them spoon-fed in black-and-white. Now, I realize that some projects – especially ones in Science Fiction and Fantasy – might require a bit of set-up as part of the foundation. World-building is no easy task, and when you have a lot of facts required so that the storyteller and the audience can begin on common ground then I can imagine that the adage “more is less” aptly applies to eliminating any confusion before our story begins.

Still, Screamers opens with quite a lot of information, and I question just how much of this data dump was truly necessary in order to establish an effective jumping off point.

Some of it appears absolutely necessary. I think it’s good to go into this story knowing where it takes place (not on Earth) with maybe even a cursory explanation of who these folks are (i.e. the good guys vs. the bad guys). Still, the downside here is that neither side is strongly identified as good or bad; and as it’s a Philip K. Dick world that does matter to a degree. His stories tend to involve a relatable central character caught up in a dark, dark world; and, sadly, all of that text was a bit … erm … meaty.

Any story worth its weight in ink has a protagonist and an antagonist: that is, truly, the Golden Rule to any good yarn. These two sides will meet and clash (to a degree) over a central conflict; yet the one hinted at in Screamers’ opening crawl gets dismissed pretty early in the effort when ‘the good guys’ choose to never fire on ‘the bad guy.’ (An adversary happens across an enemy’s bunker: though the soldiers squabble over who’s going to claim the kill, no one does.) Some of their hesitancy is owed to the circumstances that arise, but it’s handled so poorly here – the audience truly doesn’t find out about a proposed cease-fire until several minutes later – that I wondered whether or not these were good soldiers, bad soldiers, lazy soldiers, scared soldiers, etc. This mental preoccupation only served to pull my attention away from the experience, and that’s never a good opening for any picture.

Suffice it to say, I think it needed to be clearer from the beginning which side with which I identified. Once Peter Weller enters the fray – our presumed hero – I’m finally assured that he’ll be the one I’m taking this journey with; but the miss of these first few minutes had me questioning whether or not he was an effective leader. Sure, he sounds like the battle-hardened commander who’s grown a bit cynical as the war dragged on; yet I think a stronger set-up would’ve underscored his ongoing commitment to the mission.

As the picture unfolded, however, what I assumed the mission to be from the film’s set-up started shifting. (On the battlefield, they call phenomenon this ‘mission creep.’) Therein, I think I discovered why Screamers failed to find a huge audience when it enjoyed its initial theatrical run: the audience doesn’t learn what the true story is until about a third in not halfway into the picture! In the span of about 50 minutes, the goal changes from ‘war’ to ‘peace,’ then from ‘peace’ to ‘survival,’ and then from ‘survival against each other’ to ‘survival against our own creation.’ It felt like a script in search of a story – a target with an ever-shifting center – and I was befuddled by its listless narrative.

Well …

All of this is packaged in a script by Dan O’Bannon and Miguel Tejada-Flores as a war story. It’s presented both as a man-vs-man tale as well as a man-vs-machine, making it as equally ‘apocalyptic’ as it is ‘tech noir.’ But that, too, is misdirection as it becomes obvious once you grasp that the film is essential about man-vs-himself: as Screamers unspools, it’s easy to see very early on that there’s no war here. The war was fought. The war was won or it was lost (depending upon one’s perspective), and civilization (it would seem) has moved on. Screamers is more about what remains after war than it ever is about good vs. evil, and those remnants are far more interesting to examine aesthetically than typically is the war … and it’s been done masterly before by Francis Ford Coppola’s award-winning Apocalypse Now (1979).

In Apocalypse Now, Capt. Williard (Martin Sheen) is tasked with hunting down a renegade Colonel Kurtz solely to assassinate him before he can do any greater damage to United States’ reputation in the Vietnam War. The script is considered a contemporary adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness, a novel wherein the lead Marlow slowly comes to the realization that Kurtz has turned to evil yet allows the man to die of natural causes rather than (debatably) lose his own humanity by killing him. As is the case with art, we could perhaps argue all day long about the meaning of each of these works; but the sum total of their respective parts will likely always remain that Kurtz represents evil that must be vanquished – by man or by nature – in order for there ever be an honest attempt for society to right itself. Is there no justice in the universe? Well, maybe there is, but only if Kurtz dies by hook or by crook.

Eventually, Screamers’ Hendricksson finds himself in similar straits: though his war has ended, there’s another one brewing on the horizon. Yet, this soldier needs to cleanse his hands of this whole affair in order to have a chance at personal peace in a galaxy destroyed by the continuing industrialization of mankind.

The significant difference between Apocalypse Now’s Willard and Screamers’ Hendricksson – as characters – is that Willard is doing what he’s been ordered to do while Hendricksson is doing it by choice. This is no small distinction, and I’d suggest it might explain why Weller isn’t more well renowned across fandom for his work in this film as opposed to the crowd-pleasing genre entry RoboCop (1987). His Alex Murphy is a victim of crime who’s given a second chance to serve and protect by means of some serious cybernetic advancements; but the man underneath remains morally intact, requiring him to remain true to the letter of the law even through the film’s final sequence. Today’s audiences might call that pollyannish (if they know the word!), but I call it damn fine and effective storytelling.

By comparison?

In the absence of authority – which is truly the world as drawn here – regular folks expect leaders to lead. While a case could be made that Hendricksson’s choice to abandon ship was forced on him, I’d argue that I never saw him much care for anything on Sirius 6B. (Keep in mind that all of this is a screenwriter’s invention anyway, so that argument doesn’t hold much merit to begin with.) In fact, the first time we’re shown that he develops feelings for anything – Jessica (the lovely Jennifer Rubin) – it’s only after he’s confirmed that the planet no longer has anything to offer him. Not only that but it also comes to life in the last reel that a strong legal case could be made that he’s – ahem – consorting with the enemy as she turns out to be yet one more iteration of those dreaded Screamers we’re heard so much about. Is this the type of example audiences reward? A man who ignores his mission, abandons his post, and collaborates with an enemy?

Where I come from, I call that a traitor. Thank God this is only a movie!

I suspect O’Bannon and Tejada-Flores figured the audience would be okay with Hendricksson’s going AWOL given the fact that much of Sirius 6B is little more than hollowed-out industrial carcass. That added to the fact that both sides of this conflict have been savaged by a weapon that continues to evolve and appears unstoppable. (Alas, it isn’t unstoppable, as we see the commander present for every occasion where a Screamer – ahem – meets its maker. Granted, it ain’t easy, but it is possible.) Wherein other cinema heroes “find a way” to achieve the ridiculous, Hendricksson surrenders to his own pronounced cynicism, choosing to abandon the world for the safety and comfort of home … and ultimately that may be a pill too large for some viewers to swallow.

Screamers (1995) is produced by Triumph Films (a division of Sony, I believe). DVD distribution (for this particular release) is handled by Shout Factory. As for the technical specifications? The film looks and sounds fabulous; though the effects are a bit low budget and dated (yes, even for its time), they work just fine for the purposes of this story – a bunch of backwater locals on a distant planet who are largely cut off from the latest technological developments. As for the special features? Shout Factory ponies up a handful of interviews – director Christian Duguay, producer Tom Berry, co-star Jennifer Rubin, and co-screenwriter Miguel Tejada-Flores. They’re good – nothing spectacular, with Rubin’s being perhaps the least relevant – and I suppose interested parties will gobble them up.

Recommended. Screamers (1995) will not be for everyone. While it has perhaps the right amount of Philip K. Dick paranoia and skepticism, I felt the script (from Dan O’Bannon and Miguel Tejada-Flores) meandered a bit too much from point-to-point instead of presenting a very clear-cut progression from start-to-finish. I’d agree that it’s a lean, mean, fighting machine … but I guess I just expected a bit more external conflict when this one seemed overtly pre-occupied with the unstated internal ones. It does offer a solid, hard-boiled performance from Peter Weller (its lead), and that’s definitely worth a thumbs up seven days a week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed