In fact, some folks have accused me of downright hating CGI, but that's far from the truth. My issue with computerized imagery is that -- often times on some level -- it's very easy to spot, and this forces me to be pulled out of the experience. Practical effects work -- when done well -- just feels a bit more natural and organic to the whole storytelling palette. Yes, yes, and yes: I realize that to a certain degree this is most likely owed to the fact that I'm a bit older than most who sound off about film and television these days. Still, I think that the craftsmen and women who've been somewhat forgotten in the history of filmdom deserve far more credit than they've ever received, so I'm thrilled at the opportunity to help right that ship, as it were.

Not long after I published my review of 1989's Robot Jox (from Empire Pictures), one of the technicians who worked on the project reached out to me with the Information Superhighway: James Belohovek's resume includes a solid handful of features near and dear to many of us who cherish the film's from the 1980's -- The Thing, Dreamscape, The Wraith, Evil Dead II to name but a couple -- and I was thrilled at the prospect of swapping emails with him over the course of a few weeks. He graciously accepted my offer, and I wanted to share some of the reflections from a life lived at a time when quite a great deal of the industry was transitioning from work being done by hand into the era of computer graphics.

In 1979, I went to Cal Arts College to see if they could train me on the optical printer. Once I got there, I found out they didn't have a strong teacher who knew anything about blue screen (special effects). So I tried to make a short film – a commercial – of a space movie I had in mind. While preparing for it, I was making a good handful of models and miniatures to shoot. My roommate at the time was attending the animation school. One of his friends was Joe Ranft (writer, actor, and special effects). It was Joe who suggested that I should be a model maker. I have always had a fascination with miniatures, from Irwin Allen shows to Towering Inferno. Two other people in the same school arranged a meeting with a friend of theirs, John Van Vliet, over at Disney studios. We all had lunch together, and he looked over my very poor portfolio. He thought my work was very good. So I went home and prepared to build better models.

Later that evening, John called. He referred me to Susan Turner at VCE Inc. as he knew she was presently looking for a model maker. And Susan hired me to work on a saucer from John Carpenter’s The Thing.

Q: Have you always been fascinated with miniatures?

Making props and miniatures was never a ‘job’ with me, and I was having lots of fun doing them. I loved how working on and with them challenged my creative thinking. The payoff was seeing them on the big screen. I was proud to have brought my contribution to the movie. Of course, having my name in the credits was the icing on the cake.

I did find that building a miniature was only 1/3 of the challenge. Painting was the next 1/3, and finally lighting was the last 1/3. If I built a great model but it was filmed wrong or someone painted it wrong, that would destroy the illusion. Thank goodness I had a wonderful friend – Jim Aupperle – who lit and shot most of my models.

Q: Did you have a personal favorite project you were ever involved with?

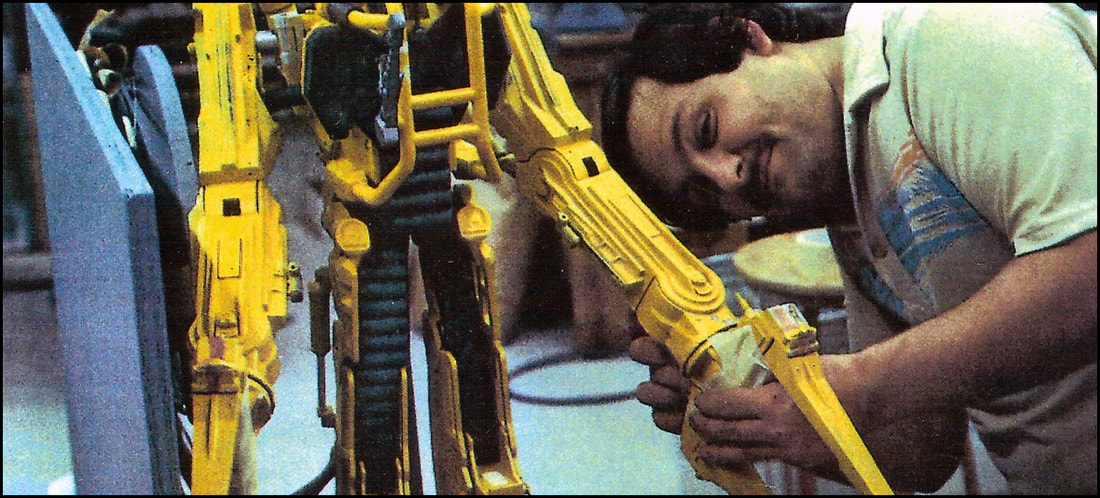

The best one was James Cameron’s Aliens (1986). I put in a lot of effort knowing it was going to be a great portfolio piece. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me. Doug Beswick let me run with it, and I had to quickly change creative gears. I started making the arm parts out of hobby plywood, but I learned quickly that using plex was the only way to go.

Each film had its interesting memories. The Thing was my first film. I was so excited to work on a real movie, and it was a space saucer to boot! I had a rough start on it. I made all the vents, but I rushed myself. At first, Susan wasn't happy with them. Instead of her firing me, she had me do most of them over and pace myself. She must have liked what I did because she hired me to help build the ice cavern featured at the end of the movie. We built it at Universal Hartland way in the backstage area where they filmed the original Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers In The 25th Century. So I got to sneak around there, see the models for those shows up close, and see how real model makers made those models. What a great introduction into movies!

After that, I went on to other projects like Dreamscape, and I even expanded my skills after finishing the miniatures I helped out doing ink and paint. Some of the cells I painted were from Return Of The Jedi (1983), Gremlins (1984), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984), Children Of The Corn (1984), and a couple Japanese movies. After working at VCE Inc. for three years, I went out on my own.

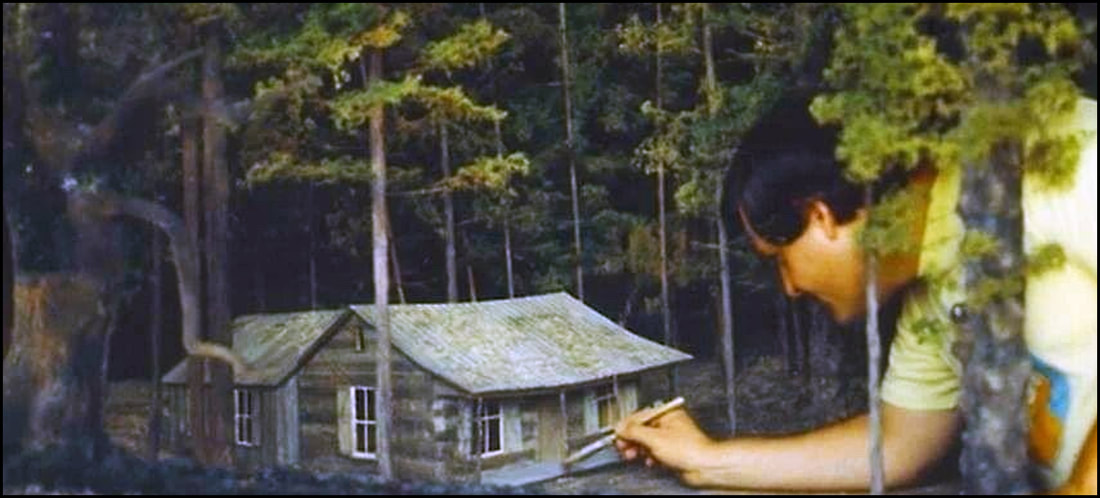

Making the cabin for Evil Dead 2 (1987) was fun. Building ‘Johnny Cab’ on Total Recall (1990) was also fun. Working on the gun/arm for RoboCop (1987) was fun. The miniatures on Beetlejuice (1988) were also fun. That got me to work at VCE and Doug Beswick’s shop. And the Addams Family 1 & 2 (1991, 1993) miniatures were also fun.

There were projects I did have lots of fun on because of the people I worked with. For example, House (1985) was a lot of fun working with all the creature effects guys. Everything from the silly jokes, the crazy music, and having clay throwing contests against the walls. It was fun, but most of the time, it was serious business.

I loved working for Doug Beswick because he had a very professional way of doing things. I felt like I was working at ILM. When I worked on Dreamscape (1984), I met Jim Aupperle. Both of us became real good friends, and we had the chance to work together on Troll (1986), Evil Dead 2, Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), and Beetlejuice. Jim was a great referral for me when it came to working on Aliens at Doug's shop since both of them had made a movie together called Planet of Dinosaurs (1977). At Doug's shop, I also worked on Drop Dead Fred (1991).

Q: How have you watched the industry evolve over the years? How have these changes impacted effects technicians?

Back in the 1980's, models were still being made by hand, not CGI like today. But all of us model makers could see the writing on the wall: either invest in a computer and 3D program, or your prospects would eventually die.

Personal computers back then were way too expensive for many of us, so working at WDI (Walt Disney Imagineering) was about the only place to go. I found myself doing that as well for several years. During that time, I had friends like Ron Thornton let me play around with his first 3D computer he bought for Babylon 5. Eventually, I chose to go into drawing in 3D for laser cutting and 3D printing. A friend that I had met way back on Addams Family 2 was going to hire me over at Wet Design. So I left WDI to go work over there and bought a 3D program called Rhino. While at Wet Design, I got to learn how to use it which was the best move in my life – to learn 3D printing.

If anyone wants to be a model maker in film, I would tell him or her to invest in a 3D program and small printer. There are so many of them out there now. And to break into film? If you're young and can work a 10-to-12 hour day, seven days a week for a few months, then it's a job for you. I don't wish to dash anyone’s hopes, but the film industry has changed so much with the producers calling the shots. The working conditions are grueling at best.

But get a good portfolio of your 3D stuff. Go to Sony or Walt Disney Studios 3D Animation Department. If you go to college like I did (California Institute of the Arts), then it's easier to break in since many of those schools have contacts in the industry. That’s how I did it. I had a couple of friends in the animation school introduce me to a guy at Disney Studios who, in turn, gave me a number to call up for my first job. Another guy in my class went to work for Greg Jein on Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). When he came back to school, he gave me Greg's number. So it still helps to make contacts.

Q: Hollywood can be infamous for its behind-the-scenes stories. Making movies can be exciting, but it can also be challenging. Do you have any memories about such challenges you can share?

When I worked on House, I met up with another friend – James Cummins – who was in charge of the creature effects. I met Jim at Cal Arts’ Halloween party back in 1981. He was wearing a face hugger and costume at the party. Also, we both worked on The Thing at Hartland. Jim had heard that I was looking for work, and he needed someone to go around and finish up some of the props. He had set up his makeup building in an empty doctor’s office on the second floor in the old town of Burbank. It’s now a shopping mall. Anyway, we were so rowdy that the owner of the store below us turned us into the fire dept! We were raided and ordered to get out because the building wasn't rated for all these chemicals that we were using. Jim convinced them to give him another day while everything was moved into his garage and backyard. What a mess! Their poor dog in the backyard had cured foam latex on his fur.

At the last shot of the show, the original contract hadn't been signed approving all our salaries and the creatures to be built. So we arrived at the soundstage but refused to do anything until the contract was signed. That was real tense for sure.

Q: I recently had the good fortune of watching and reviewing Stuart Gordon’s Robot Jox included as part of Arrow Films’ Enter The Video Store: Empire Of Screams collection. Do you have any memories about that project you can share?

On Robot Jox, I was the second model maker hired that day only by an hour. I had just come off of working on Aliens, and I was accustomed to making models like ILM would have. Doug Beswick was very professional at his approach to any job he got. So, with that in mind, I could see right away that the guy in charge of Robot Jox construction of both robots – a guy named Dennis Gordon – wasn’t very experienced at this. Originally Dave Allen asked me if I wanted to be the lead model maker because of working for Doug, but I declined. So I let Larry Bowman – who was hired first – be the lead. Larry worked for Sessoms and Sleagles (SIC) making 1/8th scale cars and trains. He was a great model maker.

Dennis's idea was to have a wood carver make the wood patterns, and we would detail the parts. I don't know the name of the wood worker, but he worked out of his trailer behind a gas station in Burbank.

So I started finishing off the first parts I got, the first being the leg pieces for Achilles. I was told to take the wood pattern and score panel lines and apply bits and pieces of styrene to detail it out. This is where I suddenly saw an iceberg of a disaster coming. I knew not to use wood for any kind of machine-looking thing. You can't score into the surface of wood, only plex. ILM uses wood to only frame and box in a model, then it’s covered with styrene. But that isn’t how they were doing it on Robot Jox.

The job was supposed to last a month. Trying to score wood took the model shop three months! After a week of trying to get a good score line in wood – the grain of the wood wasn't giving us good straight lines – Dennis had a special tool made up to put rivets across the surface of the wood pattern. I tried to warn Larry that this was a ridiculous idea, but he said do what Dennis wanted. Meanwhile, we were getting parts from the wood worker, and I received the top torso and upper shoulders of Achilles. It was another disaster because the parts didn't fit together! It was then I told Larry that we should check all the parts with each other to see if they fit together or another disaster would happen.

After a week of trying to punch rivets in the leg pattern, I gave up and told Larry that I’d fill them in give them over to the mold maker. I said Dennis can fire me if he wants to. Well, I disappointed Dennis, but I had the other model makers and Larry stand behind me. So I spent my time mostly on Achilles making the legs and most of the upper torso and arm pieces.

Then, another disaster took place: it seems that the mold maker who was making fiberglass pieces was making the parts way too thick! On Aliens, we had Tony Gardner make fiberglass pieces of the power loader parts that were potato-chip thick. It had to be light, or the cables inside wouldn't move the parts. The parts we were getting on Robot Jox were about 1/8 inch thick. These were large pieces to begin with, so this was going to make the model very heavy. After the demonstration, Larry demanded thinner pieces. The mold maker said he would try.

Once the wood worker finished making the patterns for Achilles, he began making the patterns for Alexander robot, and more model makers were hired. I was too busy trying to cut and prepare the fiberglass parts and repair any details that were lost. Honestly, I can't remember most of the order of things, but I believe this is when Ron Thornton and his English model maker buddies were hired. It seemed whatever part you worked on, you got the fiberglass part and finished it off. Then when that was done, you got the smaller version of your part that was for the animation puppet, and you finished that off.

Q: Did the production problems finally ease up?

I know that Dennis was very upset that the parts were taking way too long to do, and I think he let Ron Thornton’s crew make most of their patterns out of plex like it should have in the first place.

Around the same time we were finishing up the fiberglass pieces for Achilles, they brought in a guy to make all the aluminum skeleton and cabled joints for both robots. He started bringing in parts – the first was Achilles arm – it weighed a ton! He hooked up the cables and tried to move it, and the cable broke. Another disaster! I could see from the power loader that this armature was way too heavy and would never work. Well, word got back to the guy building the armature, and it got him really steamed up. So I backed off from trying to help with the job and did my work, just looking for a time when I could quit.

Once the armature was done, I then had to attach the fiberglass parts I had finished using the techniques I had on the power loader. I finished up doing my parts and was then asked to attach the fiberglass arm pieces onto Alexander. There was so much going wrong one day that David Allen came in and told us we should all go home. It seemed that the studio financing the project had no payroll for us. If we wanted, we could continue to work, but there was no guarantee of getting a paycheck. We all agreed to continue working, and we eventually got paid. But when it happened again, Dave ordered us home so that he could show that we were not in the building. Well, we finally got paid.

The next phase of the project was going out to the desert where they filmed the robots fighting. You had to drive out there yourself, get your own place to stay, and pay for your own food. After what I had been through up to this point, there was no way I was going out to the desert. Most of the shop quit, and the producers hired a whole new crew to build the remaining sequences and the transformation scenes. I had a lot of responsibility on the job, but some of the key people had no idea how to approach solving the problems and refused to listen to my warnings.

For me, the film was one huge frustrating event. The good thing about the job was meeting Dave Allen, making good friends with Ron Thornton, Rick Kess (another model maker), and Paul Gentry (associate effects director). I also met Ron Cobb (conceptual designer) and saw an old school friend in Steve Burg.

The bad thing was we lost a great model and prop maker, Danny Chambers. We were all working for a real low wage, but for Danny it was devastating. He was late on rent, utilities, and food. It was also very cold in the rented shop, and he caught a cold which worsened. He couldn't afford to go to a hospital, and I believe he died of pneumonia and a broken heart. I miss him very much.

Q: What advice would you give anyone trying to make a start in the business of special effects today?

I can only hope for the best for anyone wanting to be a model maker in movies. Models are still being made but few and far between in films these days so it’s hard to make a living at it now. But always have something to fall back on when there is no effects work. Everyone in the field does that.

As Super Chicken used to say: "You knew the job was dangerous when you took it.”

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed