The character of Ilya Muromets – occasionally known as Ilya of Murom or Ilya Murometz – is a knight of old drawn from a Russian fable (or ‘epic poem’) in Bylinas. (Think of him like Sir Lancelot from the Arthurian legend or perhaps even Achilles from Homer’s Iliad.) Like any mythical character, scholars have long tried to establish a link back to a living person whose life may’ve served as inspiration; but – for all intents and purposes – no true connection exists for this person. This isn’t to say that a noble life lived doesn’t need further examination; rather, it’s only meant to clarify that the proof remains elusive and perhaps it’s best to look on him and his deeds as motivation for you to follow in his legendary footsteps.

Still, not all was good as gold for the man of conscience. Initially, his was a life of some suffering as he spent the better part of three decades largely paralyzed; it wasn’t until a dying knight by the name Syvatogor possessed the young man with superhuman strength that his epic adventures truly began, eventually ending up on the road to the city of Kiev where he was ‘knighted’ by then Prince Vladimir. Even though their relationship was fraught with some controversy, Ilya – always considered a man from the people – pledged to defend that adopted city as if it were his very own.

So far as literature is concerned, Ilya was always a bit larger-than-life. Described as being the mountain of a man, he’s more revered culturally for things he stood for: integrity, faithfulness, and dedication. His word was his contract, and he always kept up his end of a bargain even if he was failed by royalty or the church. As a role model, he inspired those around him to be of service, and he never backed down from a fight, especially when that meant standing up tall and proud on behalf of Mother Russia.

Face facts, folks: the world has always needed heroes, and that’s the cloth from which Ilya was cut.

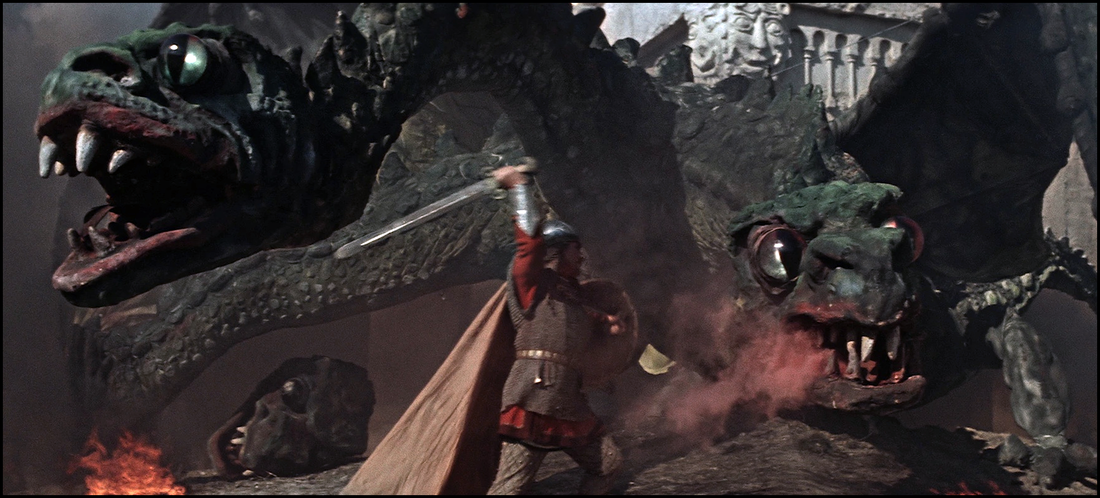

As you can imagine, his journeys are precisely what filmdom does well; and they are indeed a bit of visual legend in 1956’s Ilya Muromets: The Sword And The Dragon.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-fee, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for my final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

“A mythical knight goes on an epic journey and fights barbarian hordes in an ancient land.”

It might help modern audiences to think of Ilya Muromets as the ‘Conan The Barbarian’ from your grandparents age … well, that being if your grandparents are of Russian descent. This 1956 film captured the hero’s somewhat legendary journeys in suitably epic fashion for the era, employing what I’ve read was a cast of over one hundred thousand extras as well as over eleven thousand horses. I’ve no way to know whether or not that’s entirely accurate (keep in mind that the former Soviet Union has a history of – ahem – fudging numbers from time-to-time), but I will say that some of the flick’s impressive visuals certainly give producers a cause to boast. Its battle sequences are quite respectable, and I’d argue that they can stand alongside anything I’ve seen out of Hollywood from the era.

It's still a bit hard to dismiss some of Ilya’s campier sensibilities as they relate to storytelling from a bygone era. Screenwriter Mikhail Kochnev – this being his sole IMDB.com credit – layers on the fairy tale atmosphere a bit too thickly at times, so much so in places that it’s hard to imagine precisely what demographic he and director Alexsandr Ptushko thought they were satisfying. Some sequences hint very strongly of bedtime parables (the kind told to very young children) while others require a greater maturity to grasp the nuance. Again, I don’t offer that observation to insult; it’s just that I’m not so sure the young’uns in the audience would’ve appreciated the bigger action sequences that better move this story along to its big finish.

But about those action sequences?

If there’s any compelling reason to digest Ilya’s 90-minute tale it’s arguably for those moments as they’re when much of this truly works as a completed whole. Though some of the effects are more charming than they are effective, they still convey the sense of scope I’m sure these producers were trying to capture on film in the mid-1950’s. Even the quieter moments look good, but nothing really shines as much as big action on a grand scale, and I give the film’s latter half high marks in that respect.

Also, there are some very gifted craftsmen and women who helped create an incredible number of props, costumes, and set pieces. Nowadays, a fair amount of this background, supportive work is accomplished via CGI; while that may save a bit from the budget, nothing replaces (for this viewer, anyway) the reality of physical detail given to the swords, shields, tapestries, spears, helmets, armor, and the like. These are the kinds of extras longtime movie fans love to get their hands on – either on studio tours or celebrity auctions – precisely because they visually help transport us to another place and another time … so it’s fabulous to see so much artwork on display in this film.

Well, as a 90-minute feature, this one covers an awful lot of ground. Imagine trying to compress Peter Jackson’s deservedly revered adaptation of The Lord Of The Rings into one 90-minute film, and you get the idea. Ilya’s adventures cover decades – though we don’t see his youth (remember, he spent it mostly immobile), his life and love and marriage and rise and fall and rise again moves by in the blink of an eye – and I can’t help but wonder whether or not Ptushko’s version ended up being exactly all he’d hoped for. Indeed, the dreaded dragon doesn’t show up until very late in the picture and gets dispatched with relative ease; that trial alone could’ve made for a protracted finale, but it gets short shrift here … and I, for one, would’ve loved to have had more.

Also, I think it’s kinda/sorta safe to suggest that the picture in several speeches feels a bit like a Soviet/Pravda production. Ilya gives a fair number of speeches meant to both establish him as a character as much as he’s showing his dedication to his country. These are moments when he wanted those around him to see what he was doing as a personal sacrifice for the good of the city (i.e. the nation, the state, etc.). Knowing that this project was shot during the Cold War, I couldn’t help but wonder if fostering a sense of ‘national pride’ was part of their agenda. It certainly felt a bit overboard at times, and – though I’d never fault any storyteller for attempting to shape a public narrative – one wonders if these were sentiments organic to the tale or were they ‘requested’ from superiors and studio top brass.

Lastly, I’d be remiss if I failed to mention some of the particulars that have been passed along to me via the folks at Deaf Crocodile. What I had the good fortune of seeing is a full 4K restoration of the motion picture, complete and uncut for the very first time in the United States. I’ve only seen snippets of the original footage here and there, and I’m thrilled to say this looked and sounded incredible. I have read some additional details on the web regarding the scope/scale with which the film was originally shot; I only bring this up because there were a couple of places where players did appear somewhat distorted (either squashed slightly or elongated). Thankfully, that effect was limited to a few places, and I don’t believe it’ll affect anyone’s enjoyment of the experience.

Ilya Muromets: The Sword And The Dragon (1956) was produced by Mosfilm.

Recommended. Though I’m not a huge fan of fables, Ilya Muromets: The Sword And The Dragon certainly hit a lot of good notes, perhaps feeling like both an all-too-faithful adaptation of the Russian folk story as well as a bit-too-obvious helping of – ahem – state-sponsored propaganda. At times, it’s visually infectious, though no single actor or actress truly breaks through the noise with any singular moments. There are a few musical-style numbers: while I’ll admit I’m not a fan of the traditional musical, these small sequences didn’t bother me.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Deaf Crocodile provided me with a complimentary streaming link for Ilya Muromets: The Sword And The Dragon (1956) by request for the expressed purposes of completing this review; and their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed