Because I do prefer old films – always have and likely always will – I do exercise the benefits of having so much already written about the features. I love not only writing about film but equally treasure reading about them, especially articles and columns that teach me something about an artwork’s message, its construction, or its lasting impact. Scouring the net as much as I do has shown me that we, culturally, all have something to say about the films – big and small – that we find; and these artists have put incredible effort into composing something that they believe personally will reach out and touch us in a way only they can. Sometimes, it works. Sometimes, it doesn’t.

As a thinker, I find more joy in exploring flicks that fail.

Why? Well, that’s an easy answer. It gives me a foothold with which to consider what message I believe was intended, and then I can compose my own game plan to document how I personally believe it missed that mark. That doesn’t make me right – nor does it prove that my hypothesis is flawed in any way – but it presents you – the reader – with a point or two to ponder when you sit down and look at the flick. I’m not looking to persuade you; rather, I’m only trying to point you in a direction that might suggest relevancy. As always, you’re free to like what you like … and that’s because preferences are vastly too personal for each of us to be ignored.

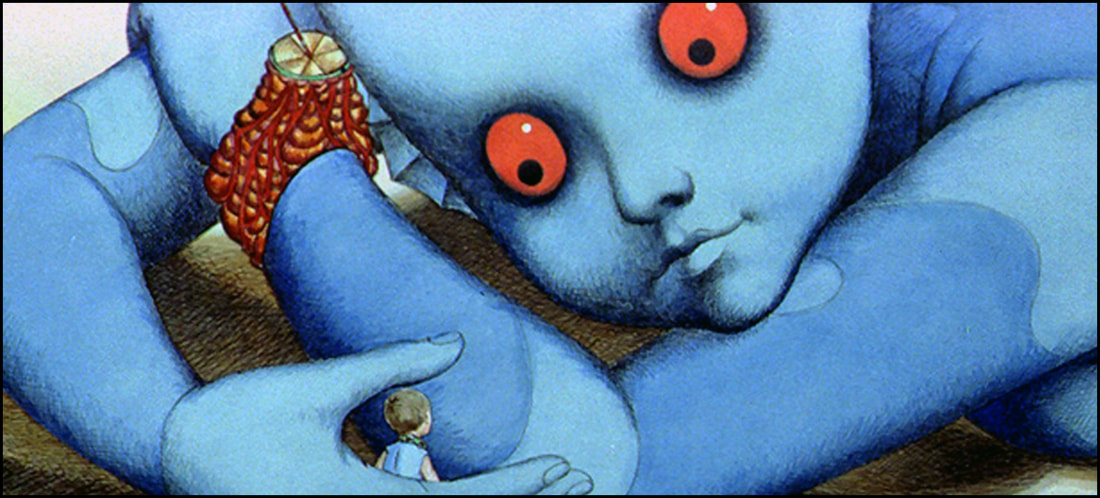

1973’s Fantastic Planet is a picture I’ve read an awful lot about over the years. Why, I can even remember – as a little guy – seeing a picture of it in an episode of Starlog Magazine (I believe it was) that intrigued me, wondering what its depicted creatures big and small could all be about. Well, I’ve finally seen it – thanks, Turner Classic Movies – and I have a little something to say about it that might not quite reconcile with what the artistic masses think of the film. But stranger things have happened, no?

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

“On a faraway planet where blue giants rule, oppressed humanoids rebel against their machine-like leaders.”

Sigh.

As can happen from time-to-time, IMDB.com and its countless contributors kinda/sorta get it wrong (to a degree, anyway), and – in the opinion of this reviewer – such is the case today.

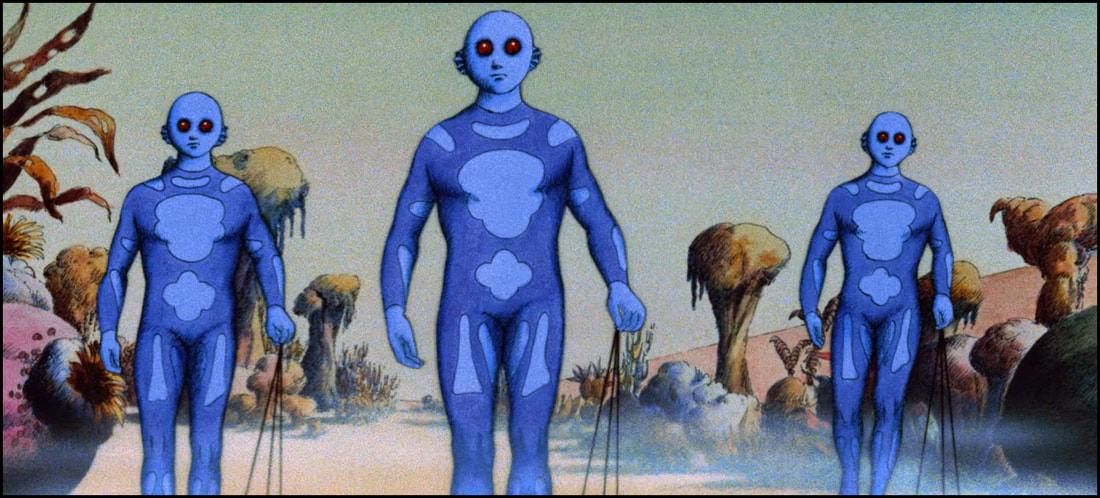

The (ahem) Fantastic Planet in question – though some may find such particulars unimportant – is called Ygam, and – if I’m being completely fair – it isn’t exactly ruled by the Draags, those aforementioned blue giants. It is their planet. This is their home. Being native to it, I’m not certain why whoever wrote the synopsis did this way, but it’s a bit misleading.

The oppressed humanoid rebels – who go by the name of Oms, in the picture – are actually humans from Earth. As best as I can recount the background, Earth of the future is apparently decimated by some conflict, and – for reasons never quite clear in the draft of this script by Roland Topor and director René Laloux (as adapted from the Stefan Wul novel) – the Draags have apparently forced immigration upon the Oms by bringing them to Ygam. (Sorry, but if this point was clarified, then I completely missed it.)

Therein lies my single greatest concern with Fantastic Planet’s premise: just how the human race got here – if we were indeed transported here – is never addressed, and this omission remains kinda/sorta at odds with everything the viewer learns of the Draags over the course of the ensuing seventy minutes.

Now, our cultural betters would likely have a field day with my argument as a good deal of film criticism for Fantastic lies around the allegory of its central message. From what I’ve come to know (from reading), Topor and Laloux sought to use this particular story as an allegory for the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia (or, at least, that’s what is widely accepted), framing the Oms as the encroached upon Czecks and their Soviet oppressors as the Oms. Of course, that’s all well and good – again, so far as this viewer is concerned – as the characters, events, and circumstances all fill out their narrative weight just fine across the parable. (I won’t belabor my review with that in any great detail as it’s out there – in spades! – for those who wish to know more. Just Google it.) But lacking a clearer picture as to why the eventually villainous Draags sought to save the human race from extinction – while treating them so poorly on Ygam – doesn’t quite reconcile with the rest of the film.

So … did the Draags take pity on us because we were such small and small-minded creatures in their eyes? At this point in the story, humans are viewed as little more than pets – though, honestly, insects would be far more appropriate given the way this story unfolds – and I kept wondering, “Why would any species as advanced as the Draags seek to import a new type of bugs to their world?” Fantastic’s script makes great bones about the fact that there are both domesticate and wild Oms – again, this highlights the emphasis on the reality that we’re a veritable infestation to their world – so why oh why would they have brought us here? Especially, why would they have even thought twice about importing us seeing what we did to our own planet?

Setting that narrative flaw aside … sure!

I’d tend to agree with so much of what’s already been written about Fantastic. Clearly, there’s an important core message to all of the affairs here, one that’s heavily centered on acceptance. The Draags seem to deem anything inconvenient to their existence as being unworthy of sharing space, and the depiction of their efforts to – quite literally – wipe out the Oms entirely are exceedingly grim. (If you haven’t heard, then let me assure you that Fantastic Planet is not an animated films for kids, unless they’re of an age wherein you and they can speak intelligently with one another afterwards.) That doesn’t quite jive with my thoughts above – if humans are so inconsequential, then why did you bring them here in the first place – but the flick very vividly invests efforts in showing a small-scale genocide very well.

Those are waters that shouldn’t be muddied.

Fantastic Planet (1973) was produced by Argos Films, Les Films Armorial, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA), and a few other participants. (For a full list, please check IMDB.com.) The film is presently available for streaming purchase (or physical media) from Amazon.com, HBO/Max, The Criterion Channel, and a host of other platforms. As for the technical specifications? I watched a recording of the film on Turner Classic Movies, and the sights and sounds were perfect from start-to-finish. Lastly, as I watched this entirely on my own as said above, there were no special features for me to consider. (Suffice it to say, I combed the internet for a handful of articles to learn more about the production.)

Recommended, but …

My single greatest caution before undertaking Fantastic Planet is to avoid any major research about the film before viewing it. (A review here and there is OK, but avoid the deep dive.) Though not a particular confusing film, it certainly gives one something to think about. At 70 minutes, I’d still caution that the story takes a bit of time to truly get going as so much of the affair plays out a bit more like vignettes strung along for a time until the true conflict emerges. Once it becomes clear that this is an exploration of cultures in existential conflict (of a sort), then it definitely gets better … though as I tried to be clear I’m not entirely comfortable with the presented reality as so many others were. A bit dark here and there … and definitely not for kids.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed