Meaning: A form of Japanese period drama

Sometimes, one has to go into a new experience with a foreign film knowing full well that he may be lost culturally. This is not to say that the story is beyond comprehension; rather, it’s only to suggest that a Japanese film may by its very nature include elements best known by a Japanese person. Like any nation’s storytellers might do, the Japanese often pull from established history in order to weave a compelling drama or melodrama; and when these efforts finally find audiences in far-off, distant lands, it’s entirely understandable how those pieces might get somewhat lost in translation.

Word: Shinobi

Meaning: Those who act in stealth

Here in the West, a great number of Japanese films exploring the rich, textural traditions of the samurai have served as inspiration for remakes and/or revisitations. Why, the much-celebrated George Lucas has been on record multiple times citing 1958’s The Hidden Fortress from Akira Kurosawa as the single greatest vision that put him well on the path to creating his Jedi Knights from the Star Wars saga. Furthermore, Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954) has enjoyed a handful of makeovers from various filmmakers, including John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960), Jean Negulesco’s The Invincible Six (1970), Jimmy T. Murakami’s Battle Beyond The Stars (1980), or Zack Snyder’s Rebel Moon (2023).

However, another uniquely Japanese persona from history – the Ninja – hasn’t enjoyed the same level of Western imitation. While there have been some modest attempts after these somewhat mysterious figures broke into pop culture in the 1960’s and 1970’s, it wasn’t until the 1980’s that they kinda/sorta emerged in some modest exploitation-style action thrillers like Enter The Ninja (1981), Revenge Of The Ninja (1983), American Ninja (1985), and even Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990). It was at this point that ninjas were here to stay – theatrically, that is – and they truly took a place in our global collective consciousness.

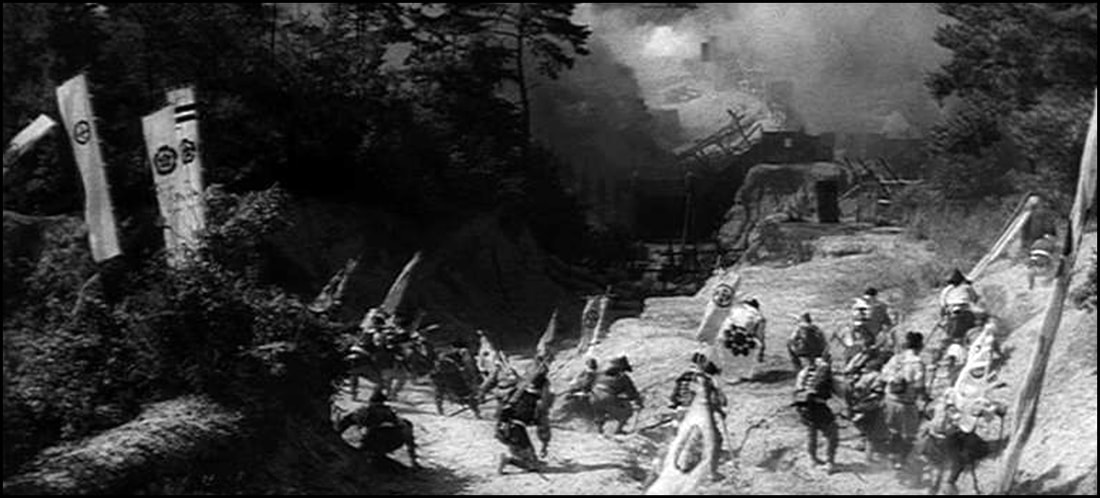

But the dirty little secret is that ninjas had somewhat made their introduction into filmdom much earlier. In fact, Wikipedia.org shows them emerging from the shadows all the way back to the 1930’s; and some might argue they finally were forced front-and-center of the subject matter with the Shinobi no Mono series of flicks (1962-1970). Having finally seen the first installment – titled Shinobi no Mono (aka Shinobi: Band Of Assassin) – I thought I’d share some remarks on this theatrical beginning.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

“A young ninja becomes embroiled in a plot to kill a tyrannical warlord. He journeys across feudal Japan, facing deceit, betrayal, and enemy ninja at every turn. Goemon must complete his mission, regain his honor, and survive.”

Without a doubt, I found this review of Shinobi to be one of the hardest I’ve ever written. Also, I’m not ashamed to admit this to the readership of SciFiHistory.Net.

It isn’t as if I’ve nothing to say about the film because – hey, you know me – nothing could be further from the truth. Instead, it’s that I found the overall experience more than a bit befuddling. This Band Of Assassins delves fairly deeply into Japanese history – both with its brief set-up and, apparently, with events spread liberally across its 100+ minute run-time – and I’m afraid my lack of knowledge might color my impressions of it slightly to the negative. After viewing, I did a bit of Googling to try and establish a greater understanding of how a few of these dates figured into the broader narrative, but – alas – I still came away just a wee bit perplexed due to a shaky grasp on peoples, places, and things.

Now, in my defense, my take does grow even dicier over the way director Satsuo Yamamoto chose to construct the piece, framing a sizable portion of the plot with voiceovers and whatnot. Some of these are meant to kinda/sorta instruct the audience as to a particular character’s mindset or to cleverly reintroduce an earlier bit of dialogue, hoping to clear up any confusion as to another’s motivations. It’s a curious choice in a few places, mostly because I thought the villain’s machinations were pretty obvious; but the end result was that it likely helped more often than it hurt, especially for those who may not have been watching as closely as others.

Essentially, Band Of Assassins tells the parallel story of two men: our protagonist Ishikawa Goemon (played by Raizô Ichikawa) and his antagonist Sandayû Momochi (Yûnosuke Itô). The two are wrapped in a power struggle that descends mostly from Momochi’s attempts to maintain the ruling seat of power over a small mountainous district secured by modest fortress walls. In order to do so – and this is specifically where Band gets a bit more complicated – actor Itô plays two roles, that of the perennial downtrodden (and seemingly constantly tired) Momochi as well as that of Fujibayashi, apparently the lord of a rival clan residing just at the bottom of the mountain. By doing so, the villain would seemingly have two forces at his disposal to enact whatever evil deeds he sets his sights upon.

Still, there’s a third key player in all of this: Oda Nobunaga (Tomisaburô Wakayama) is hellbent on uniting all of the clans into a unified force, even if it means toppling every provincial lord and overlord as far as the eye can see. Thus, Momochi knows full well that eventually the madman’s sights will turn toward the Ida clan; and it’s his aforementioned quest for ultimate power that fuels most of Band’s plots and subplots … of which there are a few.

Perhaps the best way to embrace what Band offers by way of story and characters is to understand – first and foremost – than its much-lauded exploration of ninjas and the ninja code really is secondary to the main drama, that of the two men – Momochi and the humble Goemon – forever at odds. Indeed, much of the ninja business is involved in Goemon’s plot threads: bound to serve his master, he’s given a curious promotion early in the picture (that of – believe it or not – clan accountant) which is secretly a set-up to get him to bed with Momochi’s amorous yet seriously undersexed wife Inone (Kyōko Kishada). This gives the clan leader the scheme to kill the woman – whom he no longer desires – and privately frame Goemon for her murder; as one might guess, all kinds of blackmail of the innocent man extends from hereafter, forcing this ninja-turned-bookkeeper-turned-ninja-again to violate his shinobi oath time and time again, setting the audience up for an incredible number of voiceover reminders.

(Didn’t I warn you this one was a bit hard to follow?)

Thankfully, Ichikawa and Itô are quite good in their respective roles, and it’s this moral polarity that makes Band worth the investment. Goemon flees his home village, only to discover at each and every impasse that Momochi is far from finished with him. The overlord appears whenever life starts to get livable again, only demanding more and more from the man who refuses to be broken down by the corruption. Albeit he submits relatively easily, director Yamamoto reminds the audience often of the stakes, making all of this a far more human affair that some martial arts battleground. In fact, the action is largely incidental throughout the first half of the picture; in the second half, Goemon’s failed assassination attempt of Nobunaga (set in motion by Momochi) clears the way for the big finish … yet, sadly, Goemon is more of an observer at this point and less of a participant in the bloody rampage. He gets his wishes, mind you, but redemption occurs more as a consequence of evil than anything resembling goodness.

- High-Definition digital transfer of each film presented on two discs

- Uncompressed mono PCM audio

- Interview with Shozo Ichiyama, artistic director of the Tokyo International Film Festival, about director Satsuo Yamamoto

- Visual essay on the ninja in Japanese cinema by film scholar Mance Thompson

- Interview with film critic Toshiaki Sato on star Raizo Ichikawa

- Trailers

- New and improved optional English subtitles

- Six postcards of promotional material from the films

- Reversible sleeves featuring artwork based on original promotional materials

- Limited edition booklet featuring new writing by Jonathan Clements on the Shinobi no mono series and Diane Wei Lewis on writer Tomoyoshi Murayama

- Limited Edition of 3000 copies, presented in a rigid box with full-height Scanavo cases and removable OBI strip leaving packaging free of certificates and markings

- REGION-A/B "LOCKED"

Recommended.

As I tried to be clear above, Shinobi: Band Of Assassins was a bit of a mixed bag for me. Going in blind to how much of the narrative was tied to what I can only assume are historical events kept me guessing in a few spots, so much so that I could understand others simply turning this on off out of frustration. About a quarter of the way in, I realized that the accounting of history was really secondary to what was otherwise a very relatable struggle of one good man versus one corrupt man; and the rest of the picture unspooled nicely. The film has some incredible production details – ninja houses are equipped in ways not unlike Bruce Wayne’s Wayne Manor, if you catch my drift – and both lead performances are definitely worthy of note. Stick with it if you feel the way I do right out of the gate, and I think you’ll be equally rewarded.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Radiance Films provided me with a Blu-ray copy of Shinobi: Band Of Assassins (1962) – as part of their Shinobi Trilogy Set – by request for the expressed purpose of completing this review. Their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed