Well, the simplest definition – from what I’ve been told – is that the production has somehow amassed a following over the years; but methinks we all know that the ‘hows’ and the ‘whys’ such a following shows up in the first place is vastly more complicated than that. When discussing the phenomenon, I’ve often stated that I think such projects deliver something a bit ‘out there’ for viewers, presenting them with either a subject matter or perspective that they’ve never or rarely seen elsewhere; the consequence of the experience is that some indelible connection is established between the observer and the artwork. As more and more folks find themselves drawn to it or referred there, then a faction forms around it … and the rest, as they say, is history.

A great deal has been hypothesized that cult films – at the core – should be transgressive in some way, and such a definition implies that the subject matter is taboo, falling just outside of what civil society accepts as ‘normal.’ (Erm … haven’t we also been told that ‘normal’ is a measure always in flux?) While such a descriptor might apply to a healthy contingent of cult projects, I’d argue that there still exists a plethora of entries that might only dabble with something ‘abnormal’ for its time and place; as norms grow and change, what was considered inappropriate two or three decades earlier might be passé by today’s standards. Because of the ever-changing world in which we live in, I tend to look for other traits to substantiate cult status, though I realize I might be in the critical minority on that front.

So … how exactly does a film like The Mask Of Fu Manchu (1932) acquire the cult label?

Produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the project was mired in some controversy at the time, rushed into assembly with the hope of capitalizing on the new trend of exploring full-blown Horrors on the silver screen. I’ve read (see Wikipedia.org for some details) that because of this frenzied pace there was no authentic shooting script at the inception, and the actors and actresses were often provided pages to coincide with whatever they were shooting on that day and time. That and some behind-the-scenes antics resulted in a production shutdown so that a new director could be brought in while producers continued hammering out plot details. Despite the best and worst efforts, Fu Manchu was released to the public on November 5, 1932; and it went on to some respectable box office and very well may have disappeared into film history if it hadn’t been ‘rediscovered’ in the early 1970’s when a re-release resulted in the decades-old project mustering up a bit more controversy over its portrayal of Asians.

And what a wild ride it is!

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Englishmen race to find the tomb of Genghis Khan before the sinister Fu Manchu does.”

For those unaware, the character of Fu Manchu was the creation of author Sax Rohmer (1883-1959). With the first novel written in 1913 (“The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu”), Rohmer crafted an evil supervillain that would go on to spawn a veritable franchise to which several other writers picked up the mythology and expanded on it greatly. Over a century after the evil mastermind first sprang to life in print, the character continues to pop up in novels, comics, television, and movies despite the fact that all along the way he’s had more than his share of hecklers insisting his roots are deeply mired in racism of the worst kind.

But as one who grew up on a steady diet of comic books and flawed second- and third-tier movies, I tend to see the detestable Fu Manchu – especially as portrayed here as genre legend Boris Karloff – as a campy caricature, one so entirely removed from reality that his heritage isn’t intended as a sleight so much as it was monopolized as being distinctly non-white. (Again, folks, let me be perfectly clear: I understand the complaint. I’m merely conceding that the man’s physical traits could’ve been reptilian as opposed to Asian, but as Rohmer based the character on real-life criminals he met as a reporter it is what it is.) He’s no more real than was Ming The Merciless or Sith Lord Darth Vader; and I don’t think approaching him as anything more than a stock outlaw is productive. He serves a narrative purpose – to be the visible source of evil – and little else. This is how these stories function.

So at its core the story of Mask is little more than a serialized adventure – a race against time between two opposing armies to seize the magical and mystical power of a lost era (given shape with Khan’s sword) and subvert those energies for their respective platforms. In that regard, I caution no one to look to the film as anything other than carnival fluff, much in the same way that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg brought back to the silver screen with their original Indiana Jones trilogy. Mask feels very much similar to those 80’s gems – albeit at a vastly reduced scale – and it touches on the same kind of manic, infectious energy that did other serials of the age of which I’ll mention Flash Gordon (1936), Buck Rogers (1939), and Adventures Of Captain Marvel (1941).

Furthermore, it’s this same camp sensibility of said serials that fuels the picture’s two central performances, that of Karloff and Loy. What can I say? Villains love the spotlight. I’d challenge anyone to show me evidence wherein either of these talents appear to be taking their jobs entirely seriously as their work implies otherwise. It’s all theatrical, and it works wonderfully on that level.

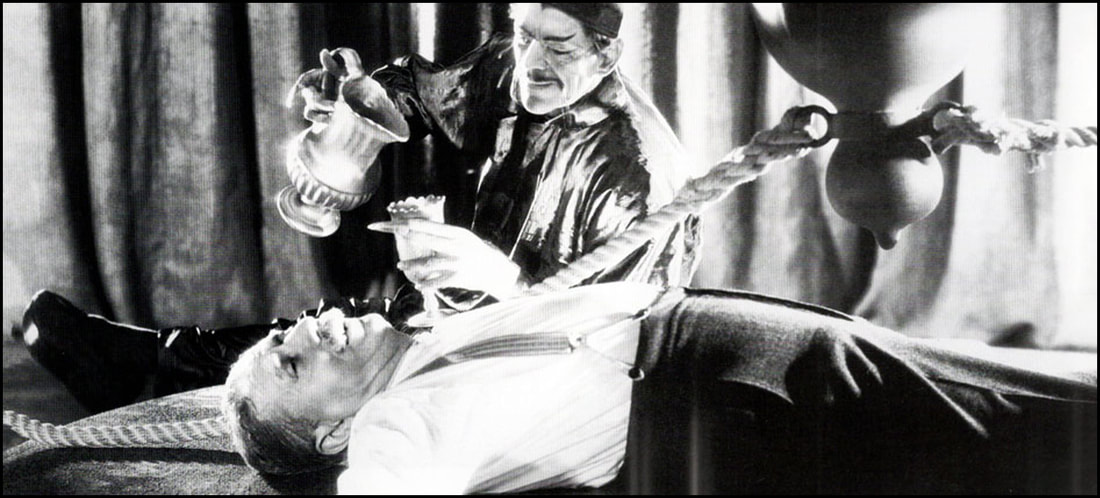

Karloff leers so easily in scenes he shares with those his character obviously despises and would do harm, making him particularly effective as the dispenser of torture on Sir Barton and (later) the hunky Granville. While I have read online the suggestion that the actor fueled these scenes with a loose homo-erotic flair, I’d have to honestly say that his dialogue only suggests here and there the fascination with the male sex. (FYI: this was pre-Code Hollywood, I’m no prude, and I’m not denying it. Again, I’m just underscoring that it’s camp, nothing is acted upon in such a manner, and – again – it is what it is.) Given that this was reportedly the actor’s first speaking role as a true screen baddie, who can seriously fault the Thespian for giving it a little something extra?

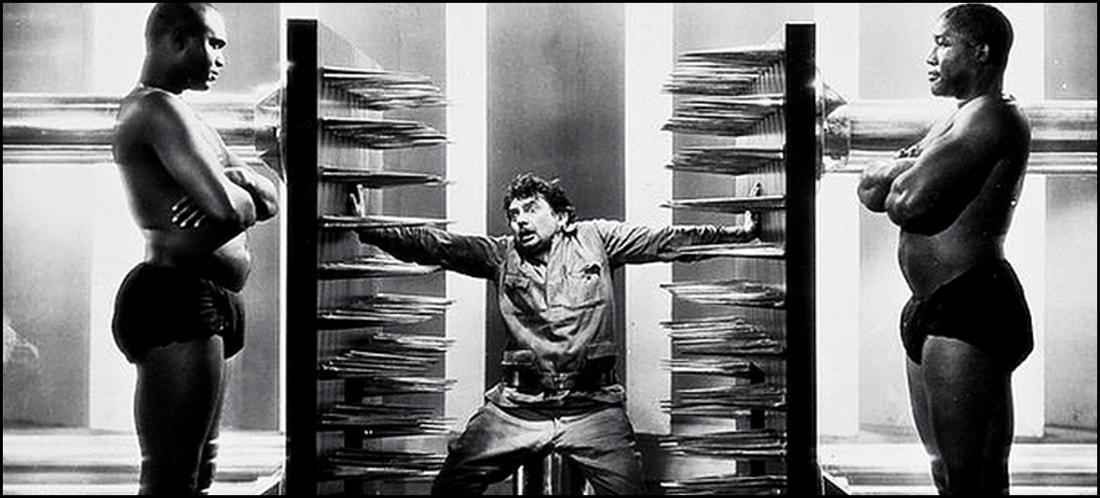

In comparison, Loy definitely gets into the act of chewing scenery here and there, but I saw her work as a bit more nuanced, perhaps even a bit more delightfully flippant in tactical ways. Clearly driven by a repressed sexual appetite, she’s drawn to the bare-chested Granville in the whip-torture scene and wants him for her own despite the wishes of an overbearing mastermind/father. While I’m not sure she relished her speeches as much as did Karloff (vocally she sounds a bit wooden and dull here and there), it still seems abundantly clear to this viewer that she sought to make Fah Lo See less authentic and more artificial … albeit with the sex drive of any thirteen-year-old male rushing headfirst into puberty.

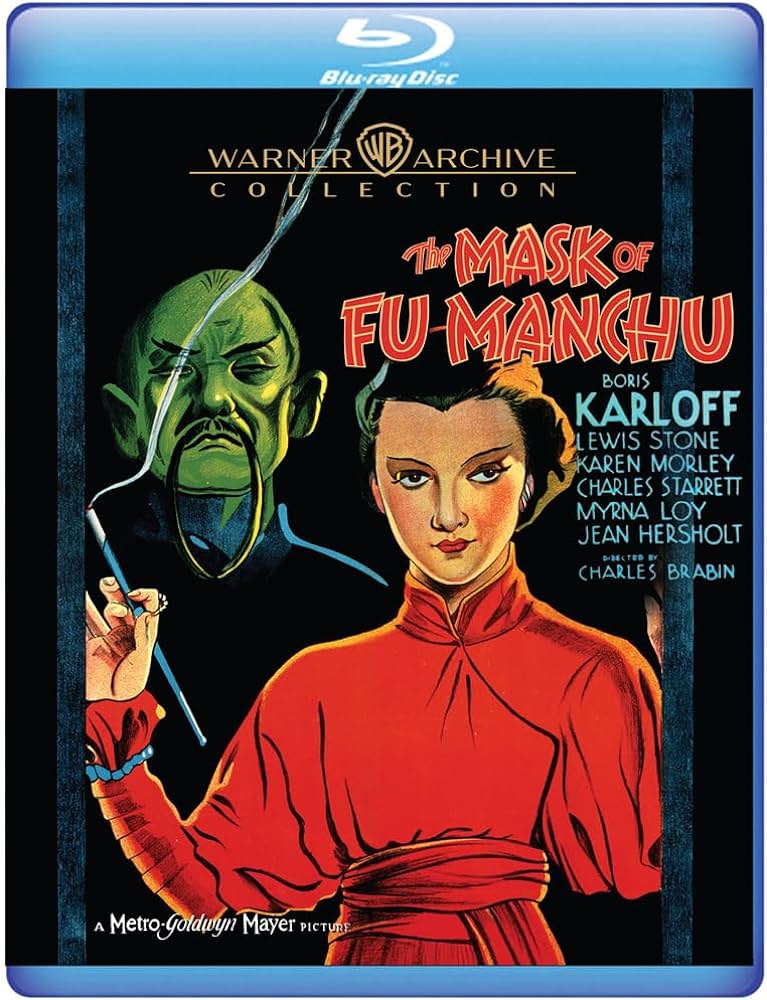

The Mask Of Fu Manchu (1932) was produced by Cosmopolitan Productions and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). DVD distribution (for this particular release) has been coordinated by the fine folks at Warner Archive. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert, I found the sights-and-sounds to what’s reported as an all-new 4K restoration from the best preservation elements to be exceptional: it all looks and sounds really good, perhaps the best it has since its original release. Lastly, if you’re looking for special features? The disc includes an audio commentary from film historian Greg Mank (it’s very solid and even occasionally very animated, a rare discussion of an older flick that’s worth the time) along with a few period cartoons and subtitles (for the feature).

Highly recommended.

If you can forgive this old man’s momentary gushing, then I hope you can appreciate that 1932’s The Mask Of Fu Manchu was a wonderful discovery. Yes, it has some cultural issues. Yes, it’s obviously drawn on inspirations from some dark moments of history. But Mask lives and breathes in that same space that’s been filled more recently by Secret Of The Incas (1954), Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984), Allan Quartermain And The Lost City Of Gold (1986), and The Mummy (1999). It’s cinematic serialized fun, and – on that level alone – it most certainly defied my expections.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Warner Archive provided me with a complimentary Blu-ray of The Mask Of Fu Manchu (1932) by request for the expressed purpose of completing this review. Their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed