Folks, because the central bugaboo of mine here at SciFiHistory.Net is promoting the history of genre entertainment, I’m sometimes challenged by a certain contingent of readers to craft reviews more toward a recounting of legacy as opposed to my actual thoughts on a certain production. In other words, some readers occasionally want me to provide more of an education about why a particular film or franchise should be as highly regarded as it is. While recounting a respectful amount of trivia might be interesting, my issue with such an approach is that information is largely available elsewhere while my resident thoughts on the picture aren’t … so I wouldn’t exactly be ‘true to my school’ if I left out part and parcel of what brings an audience to this exit off the Information Superhighway, now would I?

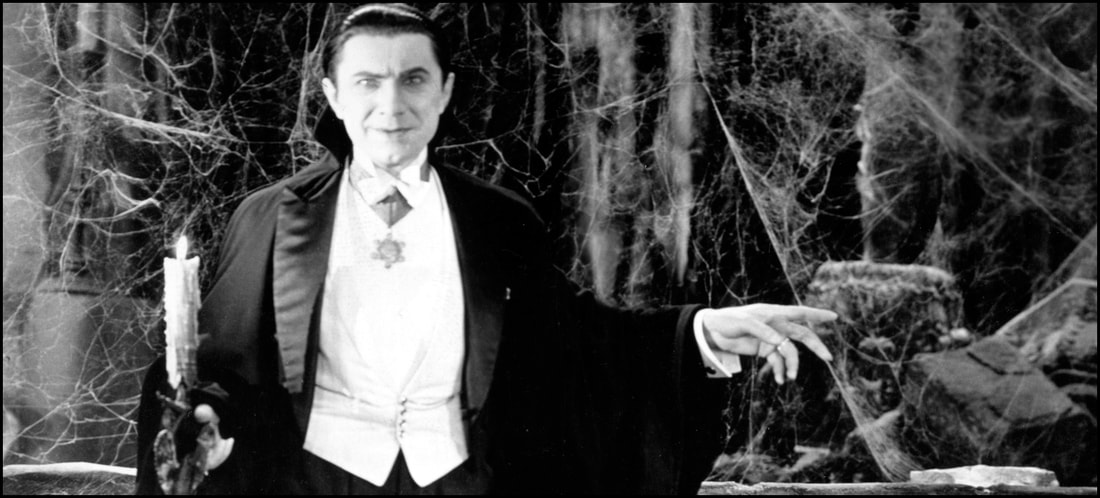

Still, there are times when I’m willing to meet the crowd in the middle, and such is the case with my look at 1931’s groundbreaking Dracula from Universal Pictures. Directed by Tod Browning (who may’ve also had his hands somewhat in developing the screenplay), the picture introduced screen legend Bela Lugosi in the role that no only made him famous but also pioneered a brand new wave of Horror releases from the studio, assuring the corporate suits for perhaps the very first time that audiences were fond of being scared silly. From what I’ve read, the film went on to spectacular box office results, becoming one of the biggest hits of that year … but the project’s journey from its beginnings in the words of Bram Stoker to prominence up in the shadows and lights is one that deserves a bit of coverage for interested parties.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for the final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Transylvanian vampire Count Dracula bends a naïve real estate agent to his will, then takes up residence at a London estate where he sleeps in his coffin by day and searches for potential victims by night.”

First published in 1897, Stoker’s Dracula certainly set fire to the world of literature in a way no one expected. I’ve read that it wasn’t exactly a publishing sensation despite some positive critical praise, but over the next few years the book arguably became regarded as the ‘source document’ for imitators, writers, and screenwriters who sought to put their own spin on the bloodsucker’s legend. It didn’t take long for some successful stage plays to draw the attention of filmmakers, though I’ve always read that studios were a bit reticent to embrace something so decidedly dark.

However, it is worth noting that outside of box office receipts (and the establishment of a franchise) Dracula didn’t exactly win accolades beyond.

It took home no Academy Awards nominations or trophies; and it wasn’t until decades later that the film took steps forward critically in the eyes of those who evaluate cinematic achievements. While the film was certainly influential in the furtherance of genre production, that first picture still seemed kinda/sorta lost in the shuffle of endless vampire flicks who perhaps basked in greater limelight. In 2000, Dracula was rightfully inducted into the U.S.’s National Film Registry – the organization that seeks to preserve pictures for their ongoing contributions to art; and over the next few years the feature was celebrated as part of the American Film Institute’s various lists celebrating the best thrills, villains, and quotes from all of cinema.

So … at this point the question becomes why did the film kinda/sorta languish in theatrical oblivion for so long?

The truth is that it didn’t – it’s the kind of title that likely had and maintained a solid following across the few generations of Horror fans that have sprung up in the interim – but, yes, maybe Dracula – the original – hasn’t been given as much love since there has been an astonishing number of variations from storytellers around the world. The classic vampire remains one of the screen’s most cherished creations, so much so that not a year goes by that audiences – home or theatrical – receive something all-new retread, reboot, or re-imagination … but not every one of them answers to the title of ‘Count.’

Count Dracula (as played by Bela Lugosi) is, apparently, looking for a change of scenery, hoping to get out of his Transylvania castle for some new digs in turn-of-the-century London. He conscripts a savvy real estate professional, Renfield (Dwight Frye); and, together, they set sail for a new land of opportunity. On the way, Renfield essentially loses his mind – a development requiring his being institutionalized upon arrival – and the Count sets up shop in the rundown Carfax Abbey that just so happens to sit on the land next door to Seward Sanitorium, the exact place where Renfield has been locked away for his own safety. Hilarity ensues … and by ‘hilarity’ I mean that the vampire gets hot and heavy in pursuit of new fleshly consorts.

Beyond Dracula and Renfield, the remainder of the cast – while good in their respective ways – don’t get much of a big screen introduction. Instead, many feel almost inserted into the affair because they’re meant to play some part – villain or victim – in some later sequence. Lucy Weston (Frances Dade) occupies the screen long enough to become one of the Count’s earliest exploits in London. Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston) exists largely as a pawn who asks questions of Professor Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) so that the audience might be kept abreast of “the science” via his exposition. And Mina Seward (Helen Chandler) is there to serve as the next tender morsel on our monster’s list even though her heart has already been promised to John Harker (David Manners). Of these supporting players, it’s only Van Helsing who truly matters, and Sloan does give viewers something to watch that both explains and explores the villainy at the center of the story.

Undoubtedly, it’s Lugosi and Frye’s work that makes the film particularly memorable. In fact, smart watchers might see this pair of performances as two sides of the same wicked coin.

Renfield’s journey through madness and, ultimately, death is handled brilliantly by Frye. In the picture’s beginning, he’s little more than your run-of-the-mill businessman, one who’ll cross an ocean in pursuit of sealing the right deal. He loses not only his soul in the process but also his mind; and we’re treated to some of Dracula’s best vignettes when he tries at all costs to both serve and defy ‘his master,’ reduced at times to a babbling fool who subsists entirely on a diet of flies and spiders. When all he wanted was to be – well – wanted, he inevitably pays the highest price possible in the film’s final reel, thrown lifeless down a grand staircase once the Count is truly finished with him.

Academics have written books on Lugosi’s work here. While I’m not learned enough to even consider that task, I will say that the actor manages a level of screen charisma not often seen outside Horror. He glares defiantly from the shadows. He stands like some immovable force not even time can crumble. There’s a physical poetry to some of his movements, perhaps incorporating some of the animal cunning long rumored to be part of a vampire’s arsenal of skills. Though his screen death is more than a bit underwhelming, it is interesting to know that he got the chance to reprise his take on the Count years later when he shared the screen with a popular comedy duo aboard Abbott And Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), a flick some have credited as giving the Universal Monsters Universe the shot in the arm it needed to rise again in theaters.

Lastly, much has been hypothesized about how Lugosi spoke when inhabiting this character, giving rise to about as unique and memorable a vocal performance as it was physical. Interestingly enough, I’ve read that this ‘accent’ was never one the actor deliberately intended: evidently, English was a second language he was learning phonetically at the time, and the result of his speech cadence – a lilting and oddly romantic tone – was just the way it came out in the process.

Recommended.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed