From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“A frustrated thriller writer wants accurate crimes for his next book, so he hypnotizes his assistant to make him commit the required crimes.”

Why, it was just the other day – when I was penning a piece about what typically draws my attention to older films as opposed to new ones – that I made an observation about narrative. It’s been my experience that older – not necessarily “classic” – productions went to great lengths with less material. They didn’t have as many bells and whistles with which to ‘shock and awe’ an audience – certainly not as much as we have today – and, thus, a talented cast and crew put in the extra effort to give their project greater substance. This doesn’t mean that it all made perfect sense; but, rather, it does imply that all involved tried to produce some end results worth greater than the price of admission.

As I pointed out, however, this doesn’t mean that those end results were designed to stand the test of time; and to a degree this is what holds 1959’s Horrors Of The Black Museum back from being anything greater than the sum of its parts. For its day, it probably worked just fine, cultivating enough interest with both its whodunnit perspective and its light theatrical trickery to generate some gasps and sighs amongst the audience. But by today’s standards? Well, this one doesn’t quite go the distance.

A city with as rich a bloody history with murders as London won’t settle on accepting bloodshed so routine, and the latest spate of killings has been growing more gruesome with each passing body. Superintendent Graham (played by Geoffrey Keen) in on-the-case for Scotland Yard, but evidence and motive seems to be more elusive than usual. That and the fact that local columnist Edmond Bancroft (Michael Gough) keeps sensationalizing the bloodshed for the delight of the city’s readership, and the police have grown weary with the writer’s constant chides about how he alone could solve the matter with his vastly superior intellect. Still, before all is said and done, Bancroft’s motivations might be called into question as it appears he might be closer to the crimes being committed than he has ever been!

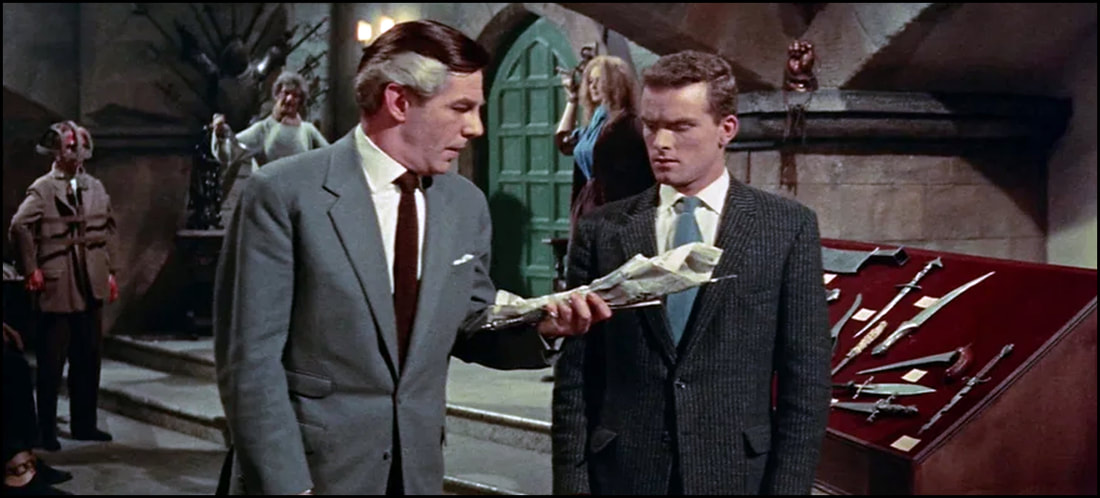

Well, if you haven’t guessed at who the guilty culprit might be, then I won’t spoil it for you – let’s just say, this one really isn’t all that difficult to predict – as Horrors Of The Black Museum pretty much descends rather quickly into little more than a melodramatic potboiler given a bit of distinction by the macabre manners in which our villain dispatches the various victims. From what I’ve read (as well as from observations heard on the disc’s commentary tracks), all of these killings were inspired by actual crimes committed by items collected and stored in Scotland Yard’s Black Museum, an assortment of murder weapons perhaps as nefarious as the nasty folks who used them for nefarious ends. Indeed, the script – by Herman Cohen and Aben Kandel – portrays Bancroft as maintaining his own private compilation of knives, axes, and whatnot – he’s enchanted with slaughter, you know, as it’s his day job – and by all appearances it’s this fascination that ultimately puts him kinda/sorta in the slaying business.

As novel an inspiration as that may’ve been in the late 1950’s when director Arthur Crabtree brought this story to the screen, I’d still argue it’s a bit … well … intellectually lazy.

For those who think that perhaps I’ve spoiled too much, let me assure you that there is a bit more to the story than what meets the eye in my above observations. Thankfully, Black Museum earns points by adding one more layer involving Bancroft’s young protégé Rick (Graham Curnow) in an interesting subplot that fleshes out just how far our learned expert has taken his interest in homicide and how one might achieve certain ends while still keeping one’s hands clean. Still, it’s a bit more magical than it is purely scientific, and I’m not convinced it won any more fans to the picture back then than it will in today’s cynical audiences.

What Black Museum is missing – again, in my estimation – is that there’s no authentic foil to Bancroft’s villainousness.

Early scenes in the picture suggest that perhaps such an intellectual counterpart – a Sherlock Holmes to Bancroft’s rather obvious Moriarity – was intended: sequences featuring Graham and the writer debating facts and figures emerging from the crime streak play nicely as two opponents trying to match one another’s grounding of facts as well as their command of police detection. They spar wonderfully when given the chance, and I suggest that a stronger script could’ve emerged wherein this dynamic could’ve served as the centerpiece for the whole affair. In some ways, it may’ve been like what audiences were inevitably treated to with David Fincher’s vastly darker Seven (1995) where investigators Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and Mills (Brad Pitt) squared off mentally against John Doe (Kevin Spacey). Given that Black Museum was filmed in the late 1950’s, it wouldn’t have had nearly the level of gore that Seven so effectively employed, but that adversarial tete e tete between the forces of good and bad would’ve given Gough and Keen’s screen time added dimension.

As it stands, Black Museum isn’t bad. It’s simply flat. You get what you expect – and then some – though there’s still enough creepiness that will likely please those who discover its charms from a bygone era.

Horrors Of The Black Museum (1959) was produced by Carmel Productions and Merton Park Studios. DVD distribution (for this particular release) has been coordinated by the fine folks at MVD Visual. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert, I found the sights-and-sounds to this new 4K restoration to be exceptionally good; all of it both looks and sounds vibrant, probably better than it ever has before. Lastly, if you’re looking for special features? The disc includes a few interviews along with two commentaries (one archival and one new), making this a worthy addition to any cineaste’s collection if interested.

Alas … only mildly recommended.

As a fan of older features, I’m honestly surprised I didn’t like Horrors Of The Black Museum (1959) a bit better than I did. Production details are good, and performances are interesting, but I still found it missing a stronger core in the character of Edmond Bancroft. When the villain isn’t fleshed out enough to make him as compelling as are his dark deeds, then I struggle to understand what motivated him – beyond personal success – to take the path less traveled. It got really close to being something truly special but slipped before hitting the mark.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at MVD Visual provided me with a complimentary Blu-ray of Horrors Of The Black Museum (1959) by request for the expressed purpose of completing this review. Their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed