And – yes, yes, and yes – I’m often asked why. (Heck, even the wifey was surprised to hear about it.)

The answer isn’t all that simple, but I’ll try to be as clear as I can.

First, Westerns are revered by many to be a uniquely American film genre; and I, as an American tend to think very highly of them. For the most part, they are structured very similar to episodes of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek: we’re introduced to the characters, and then these people are put through the paces via the classic morality play. The good and the evil are downright unmistakable, so this focus allows for storytellers to, essentially, stick to the story; and such concentrated aim allows for them to really develop the players. Granted, many of the men, women, and children might wind up being little more than stock archetypes, but every now and then they’re given a bit of room to play and something special happens.

Second, there’s a vast number of Science Fiction and Fantasy films out there for consumption that are nothing more than Westerns disguised with spaceships, ray guns, and speeders. Have you ever heard that George Lucas’ Star Wars is the quintessential Western that’s merely set in outer space? Did it escape your attention that even Gene Roddenberry and a whole plethora of television executives described Star Trek as the ‘wagon train to the stars?’ In fact, I’d argue that these two styles deserve to be looked at as opposite sides of the same coin given how much they share structurally with one another beyond just the fine print. They feel like one in the same at times, and that’s reassuring for audiences.

Lastly, there’s this little nugget of pure honesty: Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror titles are in such a limited supply – so far as the distribution outlets that I work with – that I’d not have as much to do if I didn’t relax my parameters a bit. Widening the spectrum of pictures I can ‘wax on wax off’ about allows me to draw upon like-minded features and, thus, share my insights with you – the faithful readership – in ways that delineate just how much SciFi and Fantasy and Horror both influences and is influenced by more conventional stories. It’s a small world, after all … so why not underscore how closely worker droids resemble a gunslinger’s pack mule in days from long ago? I think it’s a thing of beauty, and I can only hope you agree.

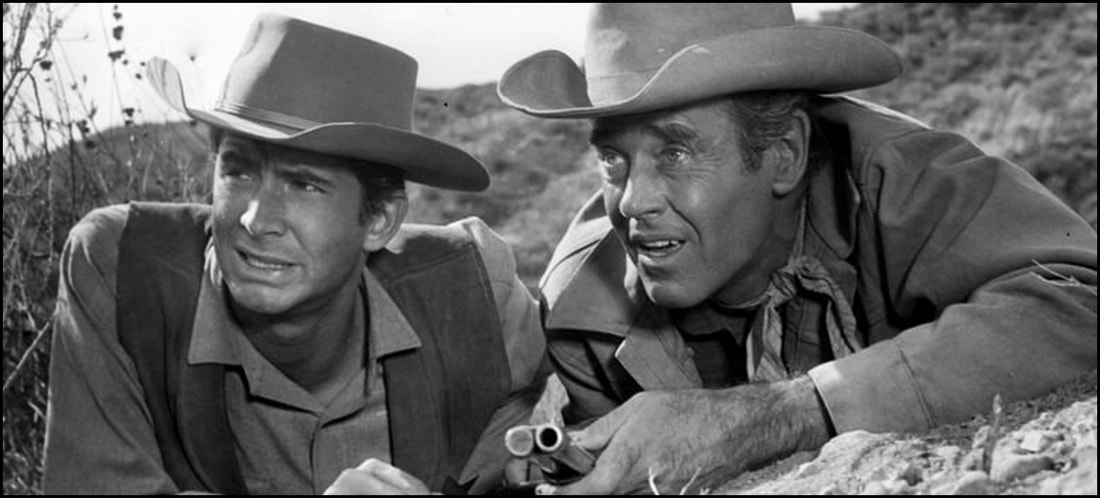

Today’s evidence: 1957’s The Tin Star, a pure oater directed by Anthony Mann and springing from the fertile imagination of Dudley Nichols, Barney Slater, and Joel Kane. Its star-studded line-up includes such luminaries as Henry Fonda, Anthony Perkins, Betsy Palmer, Neville Brand, and Lee Van Cleef. While – as a flick – it might not share an awful lot in common as I outlined above, the feature is still about as serviceable a Western as one might expect from the late 1950’s: there’s a good guy and a bad one who are destined to collide, but I’d argue that the picture plays it a bit too safe – a bit too domestic – in its middle third, so much so that I experienced a hard time staying focused on the trials of the old West’s hard knock life.

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“A cynical former sheriff turned bounty hunter helps a young, recently appointed acting sheriff with his advice, his experience, and his gun.”

Structurally, The Tin Star plays out very much like a three-act play.

In the first act, the players and situations are fully introduced. Audiences are treated to a fairly clear definition of characters, along with strong suggestions as to how they may or may not be intersecting with one another in this small, one-horse town. Traditionally, the second half is where a lot of the action and/or intrigue is supposed to happen, meaning that the writers begin truly fleshing out how these people are coming to grips with their circumstances and one another. All of those conflicts, then, are meant to build a head of steam leading to the big resolution – the final showdown – of the third act. At this point, all of the business is meant to be fully concluded, and viewers might even get a little ‘light’ coda – a casual wrap-up, often with a bit of humor or elation – as a sort-of ‘thanks for taking the ride’ with us.

Where Star really fails to resonate – at least, so far as I’m concerned – is with its second act. Instead of truly layering on the kind of substance that raises the stakes, this trio of screenwriters spend time allowing sheriff-turned-bounty-hunter Morgan Hickman (played by Henry Fonda) to establish his domestic bona fides as a man. He kinda/sorta spiritually adopts young Kip Mayfield (Michel Ray) as the son he lost years ago in a tragedy. He even kinda/sorta explores the prospect of an all-new relationship with Kip’s mother Nona (Betsy Palmer, who would go on to play the mother of Jason Voorhees in the Friday The 13th movie franchise) when she offers him a chance to stay after the town hotel brushes the man off with a cold shoulder. And he sets his sights on loosely tutoring new sheriff Ben Owens (Anthony Perkins) into the job, one he left decades ago in pursuit of a small fortune needed to save his marriage. (Hint: it didn’t, and that’s why he’s become a bit of a loner.)

Now …

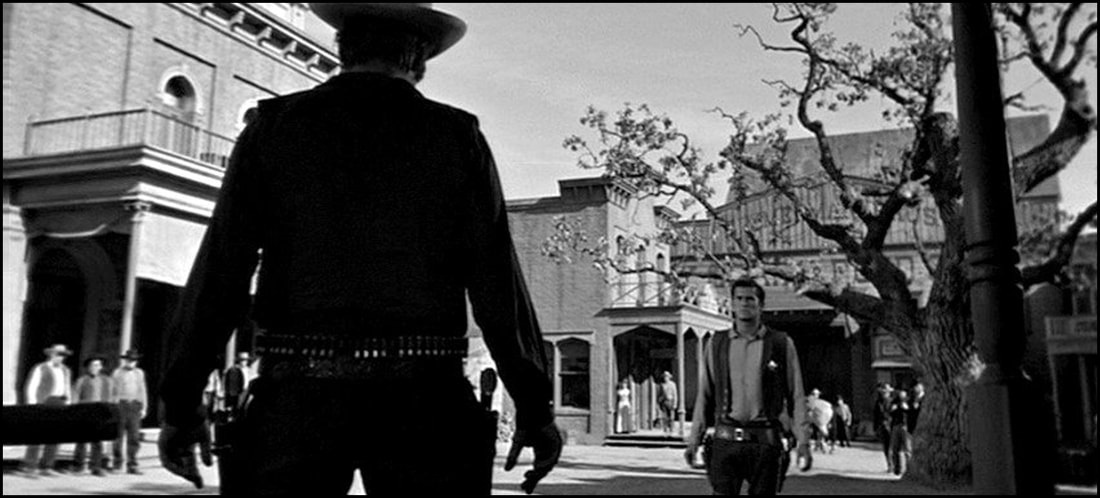

Westerns live and die on their respective last acts (i.e. the big showdown). Yes, it’s true that – to a large degree – such predictability might negatively impact the evolving shock and spectacle; but good storytellers know a thing or two about threading character motivations into the tapestry that makes for a compelling finale. Typically, guns will be blazing. Lives will be lost. Boys will be made into men, and some men will be reduced to – well – compost. That, my friends, is the ‘Circle of Life’ to the great American West; and The Tin Star, thankfully, fulfills that requirement with nothing short of a spectacular third act … one that might be among the very best the genre ever assembled.

I’m not going to bother readers with the particulars. As I think I’ve been clear, Star functions as a kinda/sorta ‘passing the torch’ style story, much in the same way that the aged Jedi Knight Obi-Wan Kenobi trained young Luke Skywalker in the ways of the Force so that he, too, could become a Jedi like his father had been long before. Substitute Fonda in for Alec Guinness and Perkins in for Mark Hamill, and you essentially have the basic foundation around which so very much of what the script presents. (The good news here is that Fonda doesn’t die, and I’m sorry if I spoiled it for you.) I do believe viewers going into this experience with full knowledge that ‘this is what you get’ might avoid some of the dissatisfaction I had with the middle passage.

What I was particularly thrilled about was how Mann’s film symbolically bookends itself with little more than a dead body.

In the somewhat somber opening moments, the bounty hunter rides into the nameless small town with a lifeless corpse thrown over the back of his spare horse. As he makes his way down the dusty streets, the residents slowly come out of their houses, the stores, the saloon, etc. all to watch as this mysterious man rides slowly past. Eventually, Hickman arrives at the sheriff’s office; and he politely explains to Owens that he’s only here to claim the fee for the escaped convict he brought in ‘dead or alive.’ It doesn’t take long before the town elders descend upon the newly appointed officer of the law, each and every one of them pontificating about what he should do about this or that, how they won’t allow for Owens to provide any aid and comfort to Hickman, and how they don’t even want ‘his type’ in their little municipality. Clearly, they see this young professional as someone they can boss around or manipulate with their respective power and stature; and Perkins plays the lawman with an appreciable degree of nebbishness.

The Tin Star (1957) was produced by Perlberg-Seaton Productions. DVD distribution (for this particular release) has been coordinated by the fine folks at Arrow Films. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert … wow! The sights and sounds to this high-definition presentation are spectacular. Extremely good. If you’re looking for special features? The disc boasts a commentary by film historian Toby Roan, and – at best – I think it’s safe to say it’s probably average in my book: the man spends a great deal of time with facts and figures of all involved, never quite dissecting the film and the story in the manner I prefer. There are also an assortment of behind-the-scenes and featurettes which make for a good education if you’re looking for such fare. I can’t speak to the efficacy of printed materials, essays, or other inserts as I was only provided a working copy of the disc … so “buyer beware” on those items.

Recommended.

The Tin Star (1957) plays it far too safe in its middle section to rank the flick anywhere near my favorite Westerns; but it opens and closes with arguably some of the very best stuff that makes oaters a genre worth some consideration. Fonda and Perkins are paired up fabulously here; and their time together alone makes this one a treasure for audiences of a certain era. Pacing in the second act – along with some average plot development – really slows down the effectiveness, but director Mann pulls out the narrative stops in the showdown that pits justice against mob rule … with justice prevailing as it should. It’s a fabulous morality play, and it should be appreciated on that level alone.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Arrow Films provided me with a complimentary copy of The Tin Star (1957) by request for the expressed purpose of completing this review. Their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed