In many respects, flicks that dominate the schedules of film festivals around the world typically qualify for this definition. This isn’t to suggest in any way that the makers of these productions and the cast and crews associated don’t wish to be seen by wider audiences; instead, it’s just to clarify that – when all is said and done – the finished product isn’t always the kind of thing that gets embraced outside the festival marketplace. No one wants to throw away good money on assembling these didactic goodies; it’s just that the audiences who want to watch and wax on about its messages, techniques, and performances are usually the festival-goers. Though their reach is finite, these viewers still hungry to discover ‘the next big thing’ for our cultural betters, so what better place is there to look than amongst their own?

For what it’s worth, I’ve had this sentiment privately agreed to by a small handful of independent filmmakers, the kind of which who have frequented that circuit on a few occasions. While that may not exactly prove my point, I think it still does imply that festival entries may have an uphill climb when it comes to impressing those who aren’t plunking down a few hundred bucks for the whole weekend engagement. John Q. Public may not have the same requirements to meet his (or her) entertainment threshold, and he’s a bit more discriminating about throwing cash away on something that may be a waste of his time. After all, he (or she) works hard for the money …

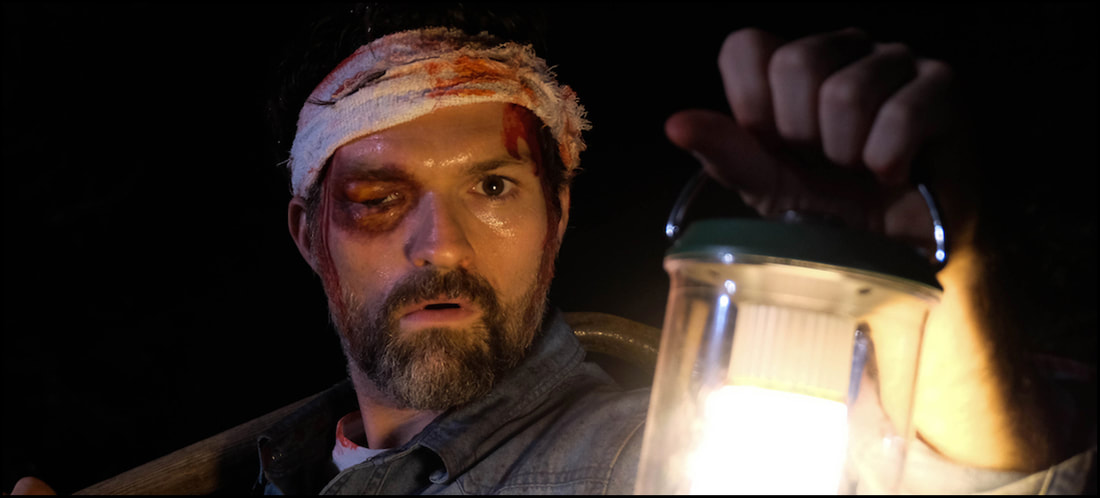

This sentiment – that of a project being conceived and executed entirely for a very specific mindset – overwhelmed me with my time watching A Wounded Fawn. Everything about it – its premise, its construction, its aesthetic, and damn well its very title – leans decidedly highbrow if not downright scholarly. While a heavy part of its ninety-minute runtime feels like an intellectual exercise, there’s just not enough meat on them bones (but there is buckets and buckets of blood) to satisfy someone just looking for a visceral escape from reality in the open arms of a traditional Horror haunt. It does have the right pieces, but it’s packaged in such a way as to demand subservience to ideas not inevitably might prove much too elusive for a knuckle-dragger like me.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the type of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last few paragraphs for my final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“A serial killer brings an unsuspecting new victim on a weekend getaway to add another body to his ever-growing count. She’s buying into his faux charms, and he’s eagerly lusting for blood. What could possibly go wrong?”

So I was thrilled at the prospect to watch and review A Wounded Fawn, the latest feature from that same writer/director Travis Stevens.

Alas, the outcome this time was far from the same.

There’s an awful lot of good in Fawn. Essentially, it’s a film told with a preamble and two acts.

The preamble rather aptly sets up this world, and it’s populated by artists, art enthusiasts, and those employed in related circles. This set-up introduces us to Bruce Ernst (Josh Ruben), a closet sociopath with a penchant for fine things and bloody murder. He’s a man that will stop at nothing to possess that which touches his deepest soul – items he describes at beautiful – and, yes, that means he’ll stoop to killing anyone who robs him of that opportunity. We watch as this smart-dressed man follows home a fellow art auction attendee, concocts a scenario to have her let him into her home, and then kills her in cold blood, all to recover The Wrath Of The Erinyes, a sculpture depicting three Furies from Greek mythology attacking a lone man.

What this intro also suggests is that Ernst may or may not be off his rocker. In the back corridor of the lady’s house, he sees a costumed figure – like something out of an ancient museum piece – bathed in red light. Is this character truly there, or is this something like a vision in the tortured mind of a depraved man? Could it be some supernatural spirit drawn mysteriously to this statue he covets, or is it nothing more than the machinations of a broken psyche? At this point, we don’t know for sure, but – as is always the case with stories of this sort – we proceed with the promise of discovery lying in wait.

Act One brings Meredith Tanning (Sarah Lind) into the fold.

An art enthusiast and (apparently) museum curator of some kind, she confesses to her pair of friends that she’s finally going away for a long weekend in hopes of a romantic tryst with a new fellow. At home, she packs her bag – complete with freshly-purchased and deliciously revealing undergarments – and privately celebrates her beau’s arrival. Lo and behold, we rather quickly learn that the homicidal Ernst is her latest paramour, and the reveal clearly amps up the tension with what now looks to be a weekend of ceremonial bloodletting, though the lady is most definitely unaware.

For reasons that honestly escape me, Stevens begins to pepper the film with some rather curious developments. Tanning begins to see things – an angry dog crossing her path on the way to car, the fleeting look at a tortured woman’s face in Ernst’s trunk, shadows suggesting movement in the forest surrounding their secluded cabin – all of which begin to suggest that either the universe is delivering signs that she’s in mounting danger or something else otherworldly is taking place. It isn’t all that long before Ernst as well is swept up in these somewhat supernatural happenings – lights turning on-and-off of their own accord, even more shadows of movement outside – which only further indicates that these two are far from alone in the wilderness. Has his gory sacrifices unleashed some esoteric beast into our universe, or is all of this little more than cosmic coincidence?

Well, we’re never really given any answers, and – before you know it – Ernst has responded both to the voices in his head and the mysterious figure he’s either summoned or shows up conveniently when he’s feeling violent. In his demented state, he kills Meredith – or has he? – and sets the stage for the befuddling Act Two.

Fawn is a flick that’s hard to talk about without spoiling some of the surprises, but – suffice it to say – Meredith’s “death” isn’t the last we see of her. It would seem that her demise opens the door to real ‘Twin Peaks’ territory as now Ernst’s three victims – all female – embody the three Furies of his coveted statue while he becomes the fallen male. (As fate – or a bad script – would have it, we learn rather clumsily in Act One that Meredith was one of the museum workers who ‘valued’ the piece before it could be sent to auction. Whether or not this truly plays into why Ernst found himself attracted to her – much less how he would’ve known of her association to it – is never clearly spelled out. It’s just one of Fawn’s rather awkward coincidences. And there are more.) Whatever the truth may be, Meredith and her angry sisters in death are back; and, as a consequence, Act Two ends up unspooling as a series of set pieces – staged dialogues between Ernst and these three entities, all with the killer’s increasingly agitated state – giving Fawn the feeling of obvious construction and not an authentic Horror experience.

As designed by Stevens and his talented cast and crew, the line between reality and fantasy blurs, but this doesn’t quite serve Fawn the way I think was beneficially intended.

Instead of making for a vivid nightmare, it instead confuses the audience which, ultimately, wants to know – in Horror, especially – what’s real and what isn’t. Frights work best when we know from where they descend; phantasmagoric sequences tend to bog chills down to the detriment of the ride. While color schemes and clever dialogue and symbolism might be important, viewers aren’t often keen on watching films that require study guides; but Fawn soldiers on, even to the point of occasionally being unwatchable … such is the case with Ernst’s inevitable demise at his own hand – or is it? – playing out over the closing credits … a time when most folks have finished their popcorn and are heading for the exits. This isn’t ‘thinking for thinking’s sake’ so much as it is continuing to make a point well after one’s already been agreed upon, and it produces the effect of warping an otherwise interesting death over to obvious intellectual bloating.

And no one likes bloating.

(Mildly) Recommended, but …

I suspect that A Wounded Fawn will, ultimately, be fairly divisive. Up to a certain point in its narrative, the plot is relatively conventional – a serial killer may or may not be manipulated by dark, supernatural forces – but once the second half begins the experience requires a fair amount of brainwork. Is it real? Is it madness? Is this literal? Or have we ventured into the territory of pure symbolism? What exactly is and is not taking place becomes an oddly personal choice – I’m never a fan of make-your-own-adventure pacing, and I don’t think a lot of regular viewers are – boiling down the whole, bloody affair to a creative exercise that may or may not have been worth the price of admission. Smartly filmed? Yes! Well performed? Absolutely! Satisfying conclusion? Well … you be the judge.

In the interests of fairness, the kind folks at Shudder provided me with complimentary streaming access to A Wounded Fawn (2022) by request for the expressed purposes of completing this review; and their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed