Wikipedia.org reports that the incestual love between a mother and her male child is called the Jocasta Complex, named after the Greek queen from the tragedy better known as Oedipus Rex. For those unawares, King Lauis and his queen (Jocasta) have a son that they quickly renounce due to the prophecy claiming that the king will eventually die at the boy’s hand. Believing they can cheat fate, the two see the infant abandoned in the wild, but before death can take hold the child is found and adopted by a shepherd. Named Oedipus, the boy eventually heads to Thebes, kills Lauis, and weds the queen, thus fulfilling the prophecy though completely unaware of his lineage. (There’s a bit more, but methinks you get the idea.)

Just as psychoanalysts have pulled the Oedipal Complex from this centuries old yarn (a boy’s affection for his mother), they’re also christened the reverse based entirely on the queen’s perspective. In Jocasta’s defense, she didn’t know (at the time) that Oedipus was her child, but I’m not here to split hairs. The lady suffers a sad ending – this is Greek tragedy, after all – but her name shines on forever in behavioral journals published around the world.

The same could be said for the eventual rise-and-fall of Señora Fourneau, the headmistress for the 19th century boarding school featured in writer/director Narciso Ibáñdez Serrador’s The House That Screamed (1969). While the motion picture stops short of definitively declaring that the mother/son relationship was incestuous, I believe there’s enough evidence provided onscreen to make for a reasonable clinical diagnosis. Just like the fate that befell Jocasta, the lovely señora likely will never be the same.

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“A strict headmistress runs a secluded school for wayward girls in 19th century France, whose students are disappearing under mysterious circumstances.”

The plight of a reviewer who watches so many films is that it eventually grows harder and harder to find one that truly both registers and says something about the world we live in; and this is why I do prefer spending so much of time with older releases made before the pomp and circumstance of computerized special effects. Simply put, storytellers had to often work harder – with vastly less resources – to craft stories that could make an impact. Granted, some of their tricks might seem downright quaint – especially by comparison to what’s so commonplace today – but their lean, mean, frightening machines gave some flammable food for thought to brains hungry for such entertainment. So while I may have been familiar with Narciso Ibáñdez Serrador’s name, I’d yet to take in one of his pictures. That now has been rectified with Arrow Film’s stellar release of The House That Screamed, and I just might consider myself a convert.

In short? I loved it.

Some of the commentary I’ve read online draw strong comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, and I think these similarities are deserving of merit. For example, Psycho – for the most part – takes place in a single locale; once audiences are delivered to the fateful Bates Motel, there’s no hope for an early check-out. (Well, not alive, anyway.) House does much of the same, delivering viewers by carriage at the onset to the secluded boarding school and then leaving them there for the duration of the tale. Additionally, both films thematically stake out – curiously enough – a pivotal shower scene with which to show that their worlds require a bit of voyeurism in order to understand their respective psychologies. Lastly, both scripts explore the bleak consequences owed entirely to a flawed relationship between mothers and sons … though House’s development is probably a bit closer to the themes of David Lynch than Hitchcock ever thought possible.

Just where – pray tell – are these ladies running to?

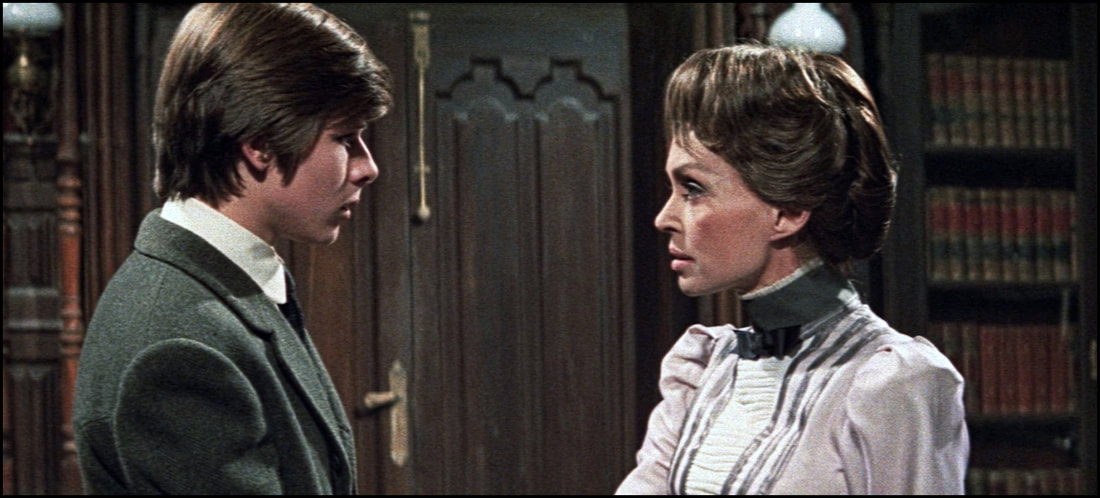

It’s a puzzle that mostly troubles her young son, Luis (played by John Moulder-Brown). Privately, he’s been doing what a growing male mind would naturally do and getting to know a few of these girls, but it’s perhaps this world’s worst kept secret as practically everyone under the roof seems to be aware of his dalliances. Of course, his mother disapproves – she keeps telling him, in no uncertain terms, that none of them will ever love him like she does – and even a few of the students in residence know of these clandestine encounters and use that knowledge to their own benefit. In such institutions, secrets become their own form of currency, and the highest prices are being paid in blood.

Without getting too deeply into the particulars, I think it’s still important to point out that House is what I’ve often called a ‘broken narrative’ film. (Don’t look it up, folks, as I think it’s honestly my own term.)

Rather than chart its path in a traditional form – meet X and follow X on her journey from start-to-finish – Serrador’s tale introduces characters (thus shifting focus) as it needs them but truly gives viewers no one player to follow the entire time. Like loss interrupts life, Serrador realigns the narrative here once or twice. Yes, it’s a bit unconventional, much like Quentin Tarantino toys with broken chronology in his Pulp Fiction (1994). Just about the time when you might think you know whose story this is, let’s just say that ‘there’s a death in the family,’ and the movie pushes you onto an adjusted path. Some of this is done to conceal the culprit’s identity – let’s just say that these young ladies aren’t just ‘disappearing,’ if you catch my drift, and there is a solid (but shrinking) handful of available suspects – so a reasonable amount of misdirection is required for the events to unfold as they do. It may not have been as organic as possible, but it was necessary in order to maintain the final twist.

Suffice it to say, you may not want to pick any favorites amongst the young, lovely lasses … because she might not last the length of the picture.

Definitively, I’m not above stating that I just had an awful lot of fun with House … once I got into it. It’s set-up is a bit slow – we spend a fair amount of time setting up the atmosphere of the boarding school and the key players – but the pay-off is grand, right up until the villain’s reveal and some pretty dark closing moments. Yes, the ending reminded me of a handful of other pictures that have concluded in the same vein, but I just loved this one’s setting and how its players wind up in each of their respective tragedies. It’s deliciously grim … and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Lastly, if you’re looking for special features?

Well, this is Arrow Films, and they rarely disappoint. I’ve not had the time to explore everything on here, but there’s an audio commentary film critic Anna Bogutskaya; two different cuts of the film (the original U.S. theatrical along with Spanish release); a series of interviews discussing the project as well as Spanish Horror; some excerpts of alternate takes of the flick; a trailer gallery; and an images gallery. The physical copy also provides some newly commissioned artwork, a mini poster, and slipcover. (Again, I can’t speak to those items as I only received an approved copy of the disc itself.) As usual, Arrow continues to please fans of cinema with their supplementals package.

Highly recommended.

As psychological Horror goes, The House That Screamed certainly benefits from an interesting though mildly predictably premise, an ensemble of talented actors and actresses, some great direction, and some fabulous production details. Its story is a somewhat fractured perspective – I was never quite certain whose story this was, and I think that’s an intention choice by the director – making it somewhat difficult as the mystery unspools to know exactly whom to follow; but its ending – while reminiscent of the kind of thing Hitchcock did best – makes it worth the wait, so far as this reviewer is concerned.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Arrow Films provided me with a complimentary pre-production Blu-ray copy of The House That Screamed (1969) by request for the expressed purposes of completing this review; and their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed