From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“A reporter who has had an affair with the daughter of the U.S. President is sent to Hungary. There he is bitten by a werewolf, and then gets transferred back to Washington, where he gets a job as press assistant to the President. Then bodies start turning up in D.C. …”

If one were to strip away any of the modern veneer found in writer/director Milton Moses Ginsberg’s The Werewolf Of Washington down to its bones, then you’d be left with the reality that – at its core – his film is honestly little more than a clever riff on the Universal Pictures’ 1941 landmark Horror/Classic The Wolf Man (starring the great Claude Rains and Lon Chaney, Jr.). Scene by scene, it pretty much matches thematically the original – even calling to mind that slow-dissolve camera trickery of the man-to-wolf transformation sequences – never veering off into unexplored territory or deviating from the formula in any measurable way. So … perhaps not all that much has really changed in the roughly three decades passage of time between that and this theatrical rehash set against the backdrop of U.S. politics? I suppose that’s as true as it is false; still, there’s an awful lot of interesting observations that could be made about monsters and men, especially when the world’s highest seats of power tend to be occupied by villains of their own respective eras.

What more is there to Werewolf than Ginsberg’s prescience?

Well … really … not much.

I sat through the director’s cut of the project (why wouldn’t I given the fact that in the materials provided he insists it’s his preferred version?), and – at 74 minutes – there isn’t much of a bloody carcass one can sink his teeth into as perhaps the auteur thought or intended. As I said, structurally, it largely parallels the journey of the first or practically any werewolf-sufferer (boy meets wolf, boy gets bit, boy becomes wolf, etc.). The fact that there’s a void of side stories and/or secondary ideas becomes pretty clear as bodies start piling up in the second half. While that’s not a complaint, per se, it’s still not a ringing endorsement; and I can’t help but wonder if some of the flick’s negative being lost for so many years truly served it best. Forgotten and/or misplaced gems usually look better in memory than they do on screens big and small, and maybe its protracted absence truly made those hearts grow fonder than was necessary.

And … kudos to anyone watching as closely as I did in spotting the masterful James Tolkan as a sunglasses-wearing agent/heavy who may or may not be serving these elected officials.

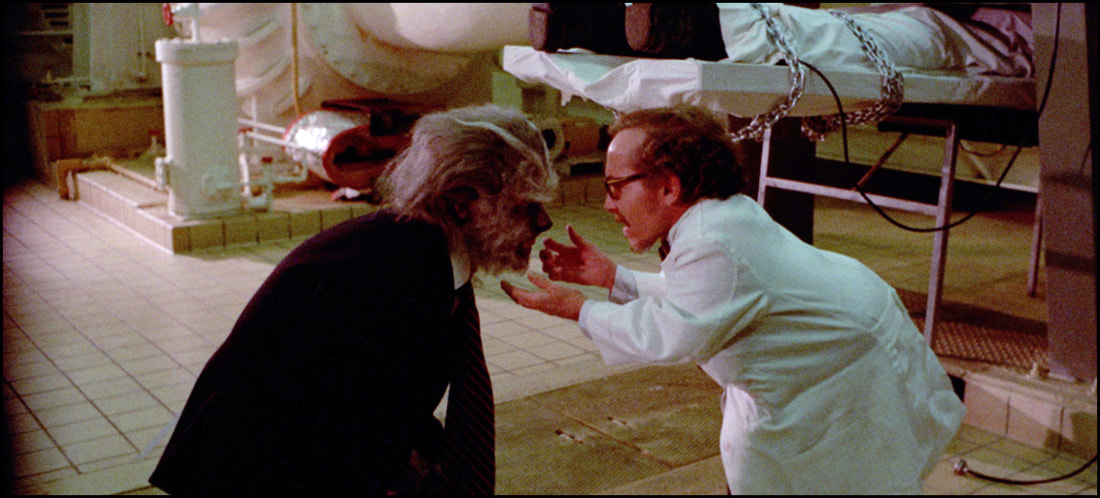

In the film’s opening remarks, Ginsberg explains that – in all of history – he’d never been so troubled as he had over The Wolf Man and Watergate, so it’s understandably why he sought out to exorcise these demons and tried to do it simultaneously. (There’s a fabulous sequence wherein our beloved werewolf seemingly finds a curiously short scientist played by Michael Dunn practicing some arcane work in what may’ve been the White House basement. Though the vignette gets a bit of a coda with the President – who gets summarily dismissed by Dunn in no small measure – it practically screams for wider context. Alas, none is provided.) Ginsberg pays homage to these moments more than he maligns them, though I can’t help but wonder if he intended something other with respect to the mocked political shenanigans. While he doesn’t quite hit the mark, I think he missed the bull’s-eye by an appreciable margin, but the Werewolf still makes for an easy one-off for anyone whose interested is piqued by the premise.

Some days, there’s nothing at all wrong with that.

The Werewolf Of Washington (1973) was produced by Diplomat Pictures / Millco. DVD distribution (for this particular release) is being coordinated via the good people at Kino Lorber. As for the technical specifications? The product packaging states that this release includes both a special director’s cut as well as a 2K restoration of the 1973 theatrical print; and – while I’m no trained video expert – I thought that the sights and sounds were quite good. Naturally, there are a few sequences that seem a bit underwhelming; but there’s nothing that overwhelming distracts from the quality of the picture. Lastly, if you’re looking for special features? There’s a brief (8 minutes) interview with Ginsberg; yes, it’s nice, but it’s short on substance, heavier on opinion. Also, there’s an interesting critical discussion between film scholars Simon Abrams and Sheila O’Malley (20 minutes) that mostly serves to put the film and its star – Stockwell – in the broader context of history; clearly, both are fond of the picture, and their enthusiasm makes for a solid short.

(Mildly) Recommended.

What one inevitably thinks about The Werewolf Of Washington will likely some ways be tied up with how much credit and/or interest gets prescribed by the obvious political allegory. Did it work, and was the comparison worthwhile? For me, I guess it worked just fine, but I just didn’t see Ginsberg’s script as being all that revelatory as it’s a pretty easy association to draw. (Politicians have always been monsters, right?) Had he taken the rest of the affair in some other direction, then perhaps I’d feel differently. Stockwell turns in some good work – perhaps a bit misdirected in some scenes – and it’s a passable enough affair to endure.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Kino Lorber provided me with a complimentary Blu-ray copy of The Werewolf Of Washington (1973) by request for the expressed purposes of completing this review; and their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed