I’ve always been fascinated by what storytellers have been able to accomplish in cinema, and it’s even more captivating to see how the tricks of their trade have evolved over time. In most respects, new technologies help to make stories more and more complex, but when you go back and take a peek at something like H.G. Wells’ Things To Come (1936), one realizes that, largely, the technology has always been there even if only to a certain degree. Sure, it may be more refined today, and there may be more ways to fool viewers; but effects have been a part of the motion picture since they began.

Perhaps there’s no better proof of that that the final third of this highly regarded film.

(NOTE: The following review will contain minor spoilers necessary solely for the discussion of plot and/or characters. If you’re the kind of reader who prefers a review entirely spoiler-free, then I’d encourage you to skip down to the last two paragraphs for my final assessment. If, however, you’re accepting of a few modest hints at ‘things to come,’ then read on …)

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“The story of a century: a decades-long second World War leaves plague and anarchy, then a rational state rebuilds civilization and attempts space travel.”

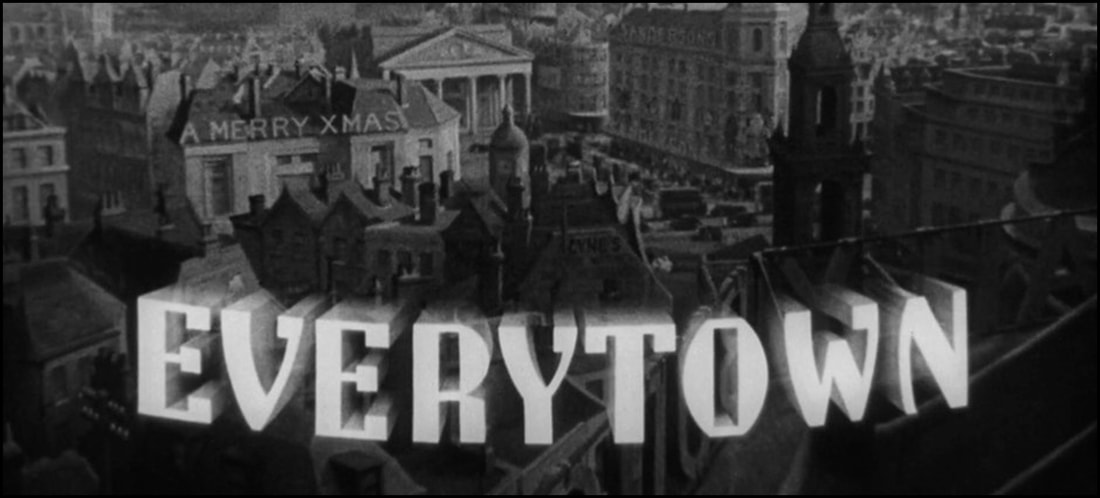

Over the course of a century, the residents of Everytown, U.S.A. experiences the highs and lows of a tumultuous civilization. When a world war promises to wipe out an entire generation, their fair city is almost entirely reduced to rubble. Decades later, a plague threatens to decimate even more. But in the distant future, the town elders rise up to deliver a message of hope for the future. Will the people embrace their destiny once more, or will they bring the promise of ‘things to come’ crashing back to Earth?

Much ado has been made over the years about Things To Come. The film adaptation was made possible only by very close collaboration between renowned science fiction author H.G. Wells and the sharpest minds of a major motion picture studio, including director William Cameron Menzies. Like Wells’ fiction, it grasps mostly at ideas that transcend the routine, trying to plot out the course mankind finds itself on while balancing the storyteller’s desire to make a definitive statement about the fragility of our world. Having read a handful of his books, I can certainly see the master’s mind at work … but – so far as this humble critic is concerned – that’s as much a weakness here as it is a strength.

Relying on too many didactic scenes, the film never legitimately posits any characters an audience can relate to other than perhaps giving each one simple trait, which hardly seems authentic. When the people don’t seem real – when they appear to be nothing more than constructs serving the plot – then the viewers are put in the untenable position of not investing any real emotion in their fates (individual or collective), and I’ll admit that it wasn’t until the film’s final section – Everytown’s future – in which I felt some attachment. That’s an awful long time to sit waiting for all of this to ‘feel’ like it isn’t preaching to me about mankind’s arrogance, warning me against mankind’s failure to rise above it all – sentiments most cynics like me already knew before the lights went dim.

However, Things To Come remains a film that’s definitely worth seeing.

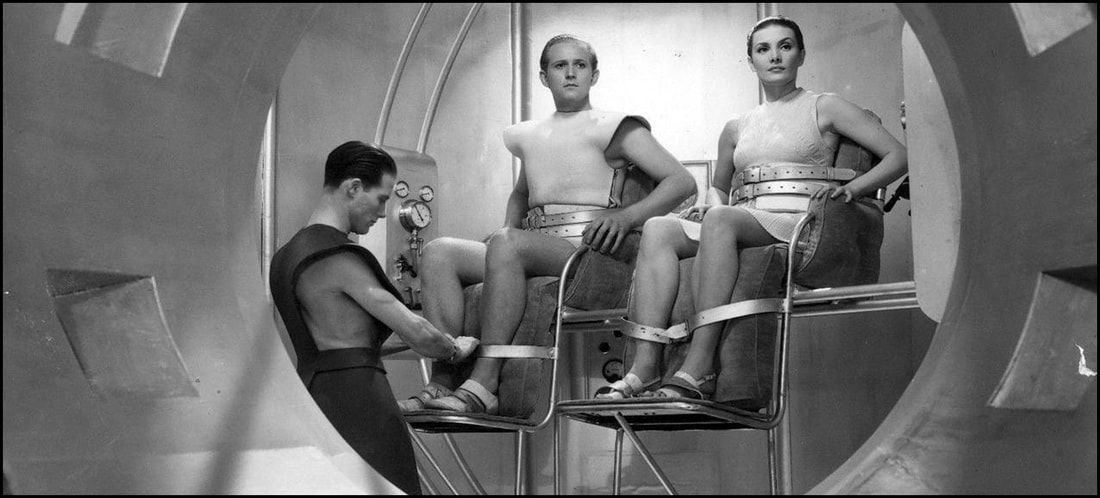

Yes, it might be painful. Yes, it might feel at times like a visit to the dentist. But the film’s structure alone is admirable. The artwork and art direction is phenomenal. Go in realizing that this story is very slow paced, and you’ll probably enjoy it a bit more than I did.

Things To Come (1936) is produced by London Film Productions. DVD distribution for this release has been handled by the good people at the Criterion Collection. As for the technical specifications, this film looks and sounds very solid with some interesting cinematography to help push the sluggish plot forward. If it’s special features you’re interested in, then this Criterion release is pretty special: there’s an audio commentary from film historian David Kalat; an interview regarding the film’s design work; a visual essay on the film’s score; some unused special effects footage; an audio recording involving “the wandering sickness” (trust me, it’s in the film); and a terrific booklet with photos and an essay from Geoffrey O’Brien.

Mildly recommended.

Others far more learned than I have said it before, but methinks it bears repeating: the only overwhelming reason to watch Things To Come (1936) is to study the film’s art direction. At 97 minutes, the first hour is a bit of a slog with several sequences going on vastly longer than they need to in order to make a relatively simple (if not predictable) point. Once the film progresses into the story’s distant future, it’s clear just how ambitious the costumers, set designers, craftspeople, and special effects folk had to work to bring this to life the way the way they did in 1936. Otherwise, I just found so very little memorable from the entire experience. A disappointment but visually interesting.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed