As I’ve mentioned previously in this space, I spent the first few years of life growing up on a farm in nowhere Illinois. Once my sister and I were approaching school age, the family picked up and moved into a nearby city (not all that large) to obviously make that easier on everyone. Naturally, this relocation also benefitted my mother and father as it meant they could get together more often with friends on Friday and Saturday nights, in which case my sister and I would be dropped off at the babysitter’s house for a few hours.

As the quiet one of the two of us, I spent most of this time propped up on the floor in front of the television. Whoever’s house it was? That person would put something he or she found appropriate on the screen (FYI: this was well before the days of home video), and I’d pretty much be expected to stay there and watch it. Thinking back, I can tell you without reservation that I can only remember two things I saw. One? Star Trek. The original series. I couldn’t tell you which episodes, but I distinctly remember Kirk and Spock. (Spock more so than Kirk, if I’m honest. I’m pretty sure it was the ears.) The other thing? Someone fixed the channel on Bert I. Gordon’s Village Of The Giants.

Of all things to remember, how do I recall that so clearly?

It’s entirely because the guy of the house – I don’t recall his name – turned to me after he figured out what was on. Bending down beside me, he pointed at the screen and told me, “Don’t grow up and turn out like these kids.”

From the product packaging:

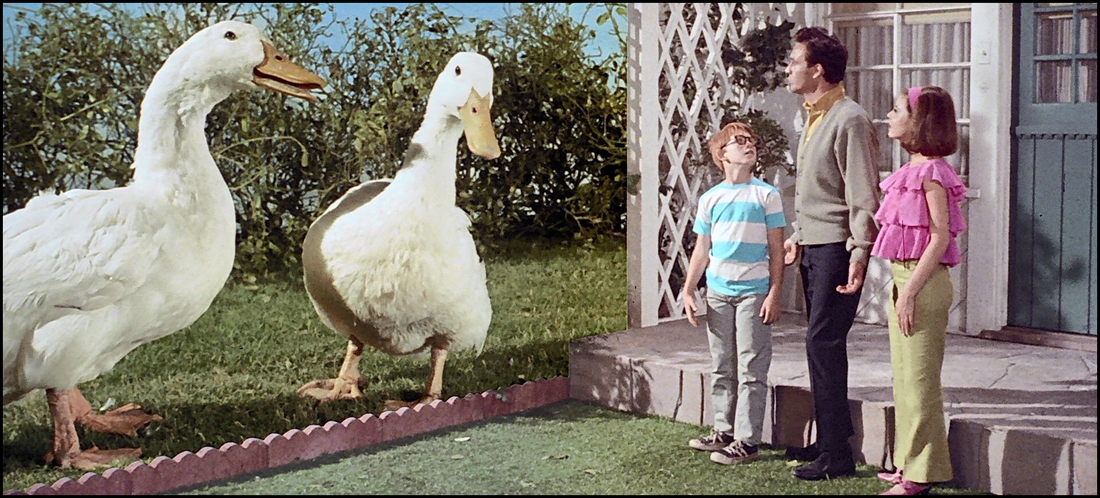

“Eleven-year-old Genius mixes up some super-goo with his chemistry set, turning cats and ducks into giants. When a group of wild teenagers see the results, they gobble it up too and turn into towering tyrants, challenging adults and making mayhem while the world desperately searches for an anti-teen antidote.”

Most readers here know of my fondness for older films.

Truth be told, Village Of The Giants isn’t one I’m all that crazy about. Though it does have a hold on me for reasons cited above, it’s an otherwise glorious failure on so many levels one would probably go crazy trying to quantify it. The acting isn’t particularly good. Its production detail isn’t all that riveting. There’s probably not a ‘big moment’ in any of it worth replicating elsewhere. And still the picture is the kind of release that endures, largely owed to a cult(ish) fascination with the finished goods.

The name Bert I. Gordon likely doesn’t resonate with most, but for fans of genre entertainment it’s one that comes up from time-to-time. Gordon’s resume includes a respectable two dozen flicks; and those genre projects vary greatly in terms of general quality much less memorability. Titles like King Dinosaur (1955), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), and The Spider (1958) are very unlikely to make any historian’s ‘best of’ listing any time soon, but they possibly had a particular relevance for audiences of their era. I watched them several times across the years of TV syndication of my youth, and I believe – though I could be wrong – Gordon’s films have been given the MST3K treatment more than any other director … and that kind of quality has got to count for something!

Adapted from ideas presented in the H.G. Wells’ novel The Food Of The Gods, this Village rather cleverly couches some biting social commentary in between moments of friction between people big and small.

Our chief antagonist, Fred (played by Beau Bridges), definitely represents the free-spirited teens of the 1960’s. They pushed back against authority of any kind. They openly doubted the words of ‘the man.’ Things like government and the civil society were to be avoided at all costs. Fred and his lot (actually a reasonably impressive roster of young talent from the day) are introduced when climbing out of a car crash, screaming in delight, dancing in the rain, and rolling around in the mud in some rhythmic display of hedonism. Once they lose interest with that, they openly announce they’ll be heading into the nearby town to cause trouble.

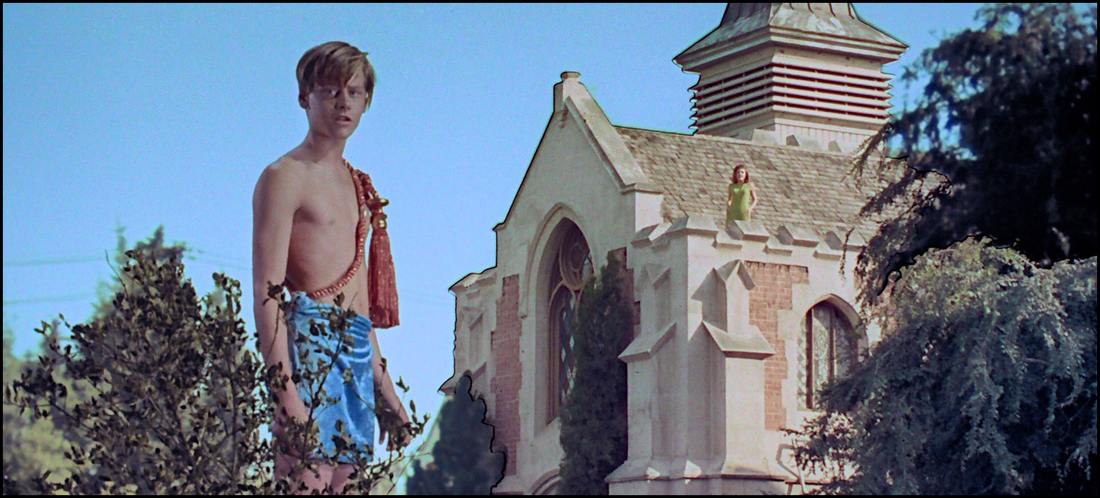

Now, this is not to say that the youth of Hainesville were necessarily any better. Clearly, there are a few bad apples in every town, and we’re soon introduced to Mike (Tommy Kirk) and Nancy (Charla Doherty) who spend their afternoon on the couch smooching quietly as Nancy’s parents are out of town for the foreseeable future. But their benign make-out session is a far, far cry from what Fred and his friends were up to, so it’s clear that what the central conflict of this story will inevitably become. It’s the counterculture versus conformity though brought to life via some fantastic concoction that makes small things grow big.

Setting aside that MacGuffin, Village becomes a project that’s easier to talk for that symbolism than much else.

Its story is a bit flat – apparently, Hainesville is the only city on the planet whose citizens express no concern nor despair with giant-sized felines, ducks, and teenagers, treating these developments as perfectly commonplace. Its production details – including effects – are a bit undercooked; there’s very little done consistently to scale in here (as it applies to the giants), and the entire look of the town is all very generic. (Having grown up in a small town, I can assure you that most have their own ‘flair.’) Lastly, its script really has no functioning and central protagonist. Mike emerges as a bland frontrunner to kinda/sorta ‘save the day,’ but it isn’t as if he sought the role nor did events craft him to serve as a leading man. Conflict works best when it’s embodied by opposites; Fred and his friends’ antics pretty much emasculate even the women in here, and the failure to centralize the force of goodness in a single voice really hurts the film’s shifting focus.

Still, it’s hard to defy Village’s charm when it comes to composing scenes where the ‘bigs’ and the ‘littles’ collide.

Proving girls just want to have fun, one of the giant-sized rebels lifts up a small townie and proceeds to dance the night away with the tiny man clinging to her bra straps for dear life, his arms astride her massive monster breasts. (It’s a scene featured prominently in the film’s advertising slicks.) When the Hainesville teens concoct a scheme to trap the lumbering Fred, they spend a sequence weaving and winding through his telephone pole sized legs. In the film’s climax, that same unfortunate townie dancing partner must descend from a building’s rafters, rappel onto those same magnificent bosoms, and drug the giant girl who ether. The things some men will do for justice!

Respectfully, it’s time like those that Village grows greater than the sum of its parts and quite probably accounts for whatever following it maintains to this day. I’d argue that many of these scenes are laced with a kind of latent, subversive ribaldry that – presented otherwise – might not have achieved censor approvals. While the rest of the film relies on a kind of childlike wholesomeness, these moments feel just a bit filthy … like a Dirty Walt Disney production, were there such a thing.

Nice work, Mr. Gordon. Nice work. If you can get it.

Recommended.

Let’s be perfectly honest with one another, shall we? Most folks aware of Village Of The Giants would point to it and proclaim that it’s because of films like this that Science Fiction and Fantasy has the jaundiced reputation it does as a genre. Still, there are those of us who’d point to the same and argue it’s because of films like this that our genre has its beloved charm! Reality is what you make of it; and, while the motion picture is as thick with flaws as are Beau Bridges monstrous, overgrown ankles, it’s still a guilty pleasure to behold. Imperfect. Hollow. Fractured. And, yet, we can’t look away …

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that the fine folks at Kino Lorber provided me with a complimentary Blu-ray of Village Of The Giants (1965) by request for the expressed purposes of completing this review; and their contribution to me in no way, shape, or form influenced my opinion of it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed