Written and directed by Peter Hyams, the story focused on the predicament of three astronauts – Charles Brubaker (played James Brolin), Peter Willis (Sam Waterston), and John Walker (O.J. Simpson) – who learn that their fabled moon shot is scientifically impossible to complete due to a life-threatening exposure to radiation. But rather than exit the Space Race in shame, their government overlords decide to proceed with televising a fake moon landing all produced at a secret facility and broadcast to the world. When the astronauts begin having second thoughts about participating in what could be the grandest hoax in human history, the mover and shakers decide it’s time to eliminate them permanently from the equation … a development that has the trio escaping their incarceration in a race against time to expose the liars and save their own lives.

Like it or not, Capricorn One tapped into a growing conspiracy that suggests that the United States actually did fake the NASA moon landings, a sentiment that continues to persist decades later. While I won’t get into the particulars of that debate (mind you: I’ve read quite a bit on the subject as it’s always interested me), it’s safe to say that such a premise has fueled a good many other theatrical and television efforts that have nibbled with the same perspective. Furthermore, storytellers have even pushed the envelope a bit further, going so far as to postulate that perhaps not you and I are wrapped up in some grand cosmic simulation but maybe the space travelers themselves could be kept in the dark with how they’ve been manipulating by secret scientific and governmental forces.

In fact, the 2014 television miniseries titled Ascension produced in part by the Syfy Channel took such an idea and really went remarkable distances with it. In the show, a veritable luxury liner launched deep in the cosmos housed hundreds of Earth’s descendants, and they were all proceeding under the perception that they were on a decades-long journey to establish a new outpost for humanity on a distant world. However, the reality of their dilemma known only to a few was that they were secretly sealed in a research facility wherein unseen scientists were privately studying the effects of deep space travel on the human psyche. (There was a bit more to it, but, essentially, this is the narrative crux of the program.) The fact of the matter that no one was actually sent to the stars – and that it was all an elaborately manufactured hoax – put it in similar stomping grounds as Capricorn One, teaching us that there are more ways to ‘skin’ a conspiracy than one.

Now I can add another title – Spain’s Órbita 9 (2017) – to the small catalogue of films that would have you believe maybe we’re not quite destined to explore the galaxy because – truth be told – maybe plumbing the depths of the human soul should truly be our Prime Directive. While a bit imperfect here and there and perhaps a bit too committed to matters of the heart that develop along the way, the picture still is an interesting portrait of morality gone awry when humanity is pushed to reconsider its options when facing a harsh existence evolving from our inadequate stewardship of the planet Earth.

From the film’s IMDB.com page citation:

“Helena has lived on a spaceship since birth 20 years ago. She meets her first human besides her dead parents when Álex repairs the oxygen supply. Things are not what they seem.”

I’ve had to point out in reviews before that the more complex a film’s story – i.e. its premise, its science, its hard embrace of politics, etc. – then the more likely some of its nuances are likely going to wind up lost in translation. While lines of dialogue get effectively translated from one language to another, there’s occasionally the problem that something now said in English – fitting the time and mouth movements of an actor speaking in their native tongue – won’t precisely convey everything needed for a development or plot twist to make perfect sense. At best, subtitles and dubbing are imperfect techniques, and still they’re the best we’re able to do in allowing stories to cross borders from one nation to another.

Though I could be wrong, I suspect that’s the case with a small portion of Órbita 9. Writer/director Hatem Khraiche has structured a morally and (mildly) politically-charged thriller that in many ways only uses the framework of the study of space travel to postulate a world wherein its simpler ‘boy meets girl’ story gets overshadowed by understandably meatier issues. Sadly, there’s a vagueness to a good deal of it – what’s precisely happened to our world that’s required mankind to consider abandoning it; how is it that such a massively complex survival program has been relegated to such a small number of scientists; why has this possible doom produced so little interest from the general public; etc. – and I found it hard to believe that some of these issues were passed over with nothing more than a casual line of dialogue here or there. This is the kind of story that probably would work better in novel format wherein storytellers have a easier time ‘getting into the heads’ of multiple characters; as this one develops, I never quite got a hold of each player’s psychology, and I feel a bit more was required for clarity.

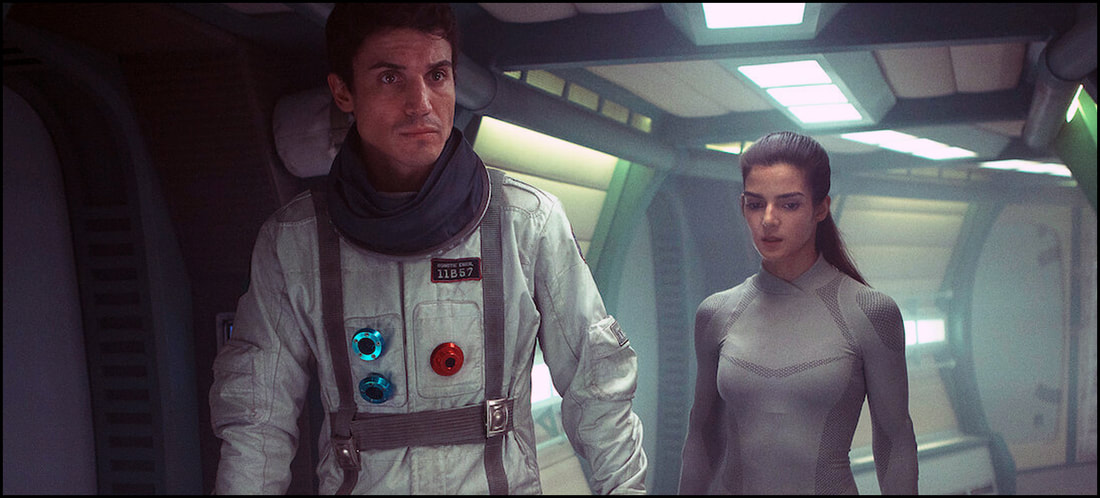

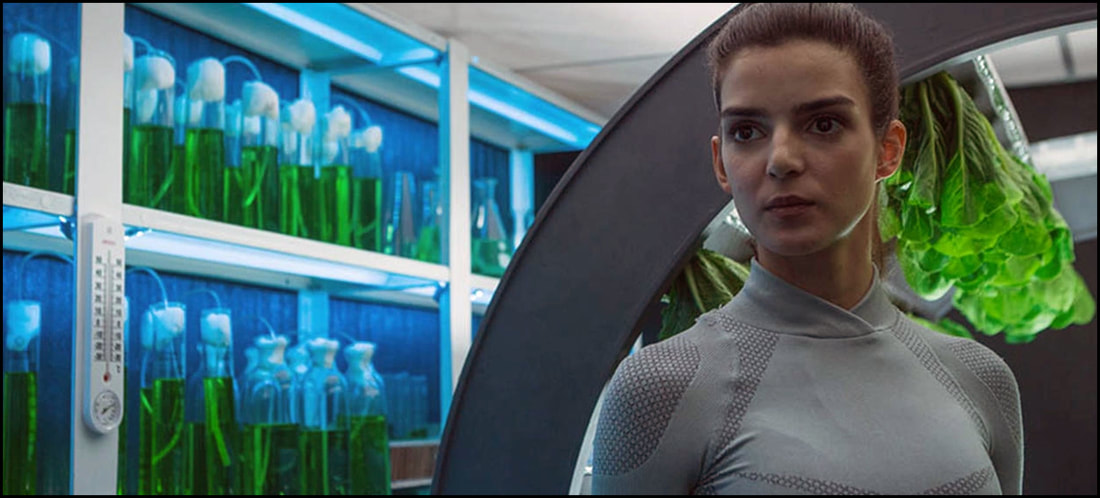

Álex (Álex González) is the shuttlecraft technician that’s been dispatched to repair a faulty air purification module aboard Helena’s (Clara Lago) spacecraft. As he’s the first human she’s come into contact with in years (her parents abandoned the deep-space journey when she was very young in order to give her the air and food supply necessary for successful completion), she’s understandably intrigued and eventually smitten with him. Against his better judgment, he allows her into his temporary chambers aboard the spaceship, where they inevitably do what boys and girls do best. But once he disembarks, the audience discovers that Helena is little more than a guinea pig: her shuttle is not out amongst the heavens but, rather, in a subterranean bunker where Álex and Hugo (Andrés Parra) have been studying the effects of long-term isolation on individuals. Apparently, such journeys have not boded well on our species, and these two scientists have been tasked with figuring out how to solve this impasse in order to ensure our survival from a future cataclysm.

By borrowing the tapestry of Science Fiction, Órbita 9 does occasionally feel like a solid conspiracy yarn. This organization apparently has the backing of some global cabal, and the compound itself has all the markings of the usual secret government facility that’s been tucked away somewhere in the wilds at the behest of the military-industrial complex. Khraiche’s script makes some allusions to the fact that the research has been going on for some time – there are more bunkers equipped with shuttle interiors that Álex monitors privately from his apartment – and, when necessary, it becomes clear that those involved at the highest levels of the operation aren’t opposed to using lethal force to obtain whatever objectives they deem necessary. Still, I just wish all involved could’ve gone to great lengths to clear up some confusion they create along the way.

There are other developments that kinda/sorta come out of nowhere; and, sadly, they, too, don’t get the kind of dissection that would’ve elevated the film to the point of seriously considering this world as it gets postulated here. Issues of cloning and the efficacy of research are unfortunate victims of trying to somehow find a way to give these two characters a somewhat Hollywood happy ending – one where love can still triumph over all even in the face of catastrophe – when things were headed well on the path to looking decidedly grim for all of us. At 95 minutes, Khraiche and his cast and crew breeze over the material, never pausing for any real measure of reflection but instead pushing ever onward with the hope that no one – audience included – will pause to ask important questions much less seek the proper answers. Why, it’s almost like knowledge wasn’t required so long as our two good looking leads cared about one another, and that’s a disappointment.

In a world where intentions matter most, Órbita 9 strives to give everything the proper emotional context – good guys still exist, bad guys will stop at nothing, and love is all you need – leaving the coldly clinical examination of doing what’s right for all of mankind kicked to the curb. Oh, they’ll happily manufacture a magical ending to put the proper spin on everyone’s best efforts, but pardon me if I point out the end result felt way too sugary for everything that came before that big finish.

Orbiter 9 (aka Órbita 9) (2017) was produced by Cactus Flower, Dynamo, Mono Films, and Telefonica Studios. The film shows as presently available for streaming on the Netflix website. As for the technical specifications? While I’m no trained video expert, I found the sights-and-sounds to be of exceptional quality from start-to-finish. Lastly, as for the special features? Given the fact that I enjoyed this viewing via streaming, there were no special features under consideration.

Recommended.

Órbita 9 (2017) ignores what it does best – setting the stage for a true moral quandary of the ages – when love rears its ugly head as it is prone to do at the movies. Intent on looking good and perhaps presenting Science Fiction as a great night out for the dating public, it squanders the heavy potential in favor of sticking to easy landings for its photogenic leads. Surprisingly, it still works effectively as a thriller when it needs to, but I really wanted to see the film that it looked like it was going to be without descending into the somewhat paint-by-numbers arena of silver screen romances. Nothing ventured means nothing gained … and who knows if the human race will survive long enough to spare itself from our otherwise inevitable doom.

In the interests of fairness, I’m pleased to disclose that I’m beholden to no one for this review of Orbiter 9 (2017) as I streamed it via my very own subscription to Netflix.

-- EZ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed